A River’s Dreamscape

A River’s Dreamscape

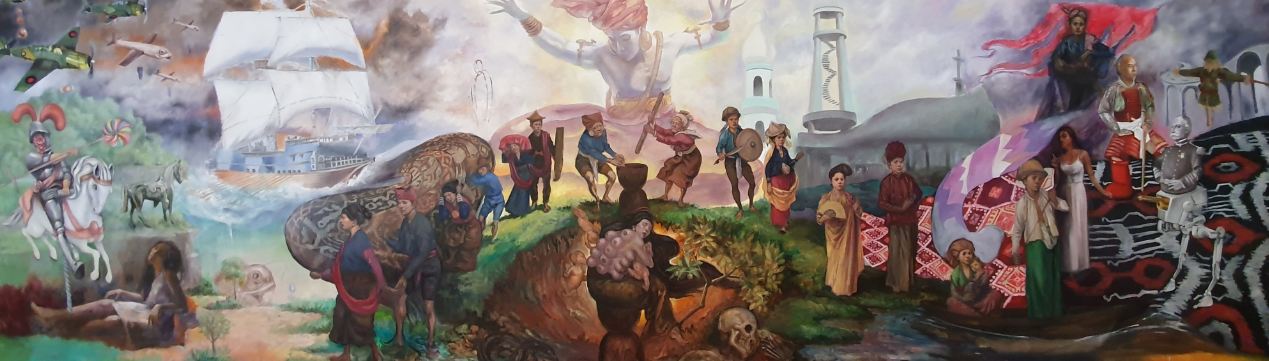

An android American-colonial soldier marches silently, tribal gods and primeval ancestors spring out of the canvas, while a faceless pin-up girl poses with a golden toilet bowl. A river of indigenous fabric runs across the two panels, connecting, disconnecting, confusing, and revealing imageries and narratives. The viewer is at first disoriented at the marching symbols, yet the mural beckons, and now completely gripped by the current of the same river that runs the canvas, the viewer surrenders to this aesthetic rebellion.

“The Silent Witness” is a collaborative artwork of ten artists from different artistic styles and personal motivations. Coming together to tell this story and ideology, are several members of Piguras Davao, an organization of figure artists from Davao City: Dominic Turno, Alfred Galvez, Dominick Pilapil, Kim Vale, Rene Pilapil, Rey Gallardo Bollozos, Mark Tolentino, Bryan Cabreta, King Nelson Duyan, and Raymund Ric Bisnar. This oil-in-canvas mural is a 2-panel work measuring 6 feet by 20 feet each, and takes its inspiration from the rich history of Davao, including indigenous mythologies, popular culture, and surreal symbolisms.

There is an intensity in the painting – in the images, the narratives, and the strongly expressive language in vibrant color, the depth of insight, and the deliberate telling of the passage of time. “The Silent Witness” is a narrative mural which tells the story of a place, or perhaps it is visual poetry, with the images signifying a complex of local histories, recollections, and aspirations.

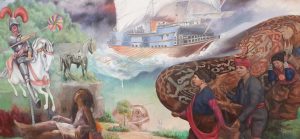

A central figure in each panel looms over the rest of the elements and draws our attention to the dialectic of the two panels. In the first panel, the central figure is the Bagobo creator god, Manama, with his arms outstretched willing creation to being. The first man and woman, the Mona, is below the creator god, and with their pounding of the ubiquitous rice mortar, a multitude of ancient ancestors descend to become progenitors of different Mindanao peoples, unique in their differences. While below the images of the first parents lie the final mother of all, Mebuyan, Bagobo goddess of the underworld, hundred-breasted, benevolent chthonic mother, psychopomp who guides and purifies the dead. Other figures in this panel are familiar historical imageries, like the ships of the Spanish conquistadores, American fighter planes, Islamic and Christian sacred places, and Arab and Chinese traders. Interestingly, the images do not follow a linear narrative. American-colonial figures are grouped together with Spanish soldiers, and ancient sultans seat with a Japanese samurai warrior. In this translation of our local history, a fighter plane morphs into a giant fish, a conquistador rides a mechanical horse from a carousel, and a decorated American general has robot feet straight out of a Star Wars movie.

A central figure in each panel looms over the rest of the elements and draws our attention to the dialectic of the two panels. In the first panel, the central figure is the Bagobo creator god, Manama, with his arms outstretched willing creation to being. The first man and woman, the Mona, is below the creator god, and with their pounding of the ubiquitous rice mortar, a multitude of ancient ancestors descend to become progenitors of different Mindanao peoples, unique in their differences. While below the images of the first parents lie the final mother of all, Mebuyan, Bagobo goddess of the underworld, hundred-breasted, benevolent chthonic mother, psychopomp who guides and purifies the dead. Other figures in this panel are familiar historical imageries, like the ships of the Spanish conquistadores, American fighter planes, Islamic and Christian sacred places, and Arab and Chinese traders. Interestingly, the images do not follow a linear narrative. American-colonial figures are grouped together with Spanish soldiers, and ancient sultans seat with a Japanese samurai warrior. In this translation of our local history, a fighter plane morphs into a giant fish, a conquistador rides a mechanical horse from a carousel, and a decorated American general has robot feet straight out of a Star Wars movie.

The first panel is recollection – but dreamlike, muddied, yet surprisingly akin to the texture and drama of our personal memories.

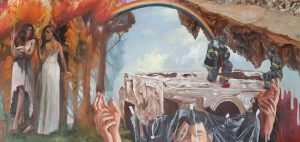

The second panel features two large elements that capture our attention: the image of Libertas mirroring the outstretched arms of Manama on the other panel, and the two human figures in a boat reminding us of the Manunggul jar. If the first panel surprises us with its cognitive dissonances, the second panel provokes and disturbs with its density of implications, hints, and fleeting seductive physiognomies. The figures on the boat riding the river of tnalak – a dream textile of the Tboli people – connect the two panels. We are the boat figures riding this history-dreamscape. The human figures in the Manunggul jar are on their way to the netherworld, but here our journey is towards awareness of the  present. In this landscape, Libertas, symbolizing freedom, is an ideal and a destination, where the river of our convoluted histories end. Surrounding this central figure are more surreal images: a woman lies dead, a hollow man is consumed by darkness, a lumad child devours a hamburger, while white-clad diwatas seduce us in a grove. The language of this landscape evokes an experience of the real with the texture of a dream following illogical associations as they appear in the canvas. Crowning this composition is a symmetrical configuration of a Naga (indigenous dragon) okir design and a Chinese-style dragon facing each other, mirroring, or perhaps confronting each other – the local meeting the global imagineries. One wonders whether these are deliriums of madmen or our own monologues that question our present individual and societal conditions.

present. In this landscape, Libertas, symbolizing freedom, is an ideal and a destination, where the river of our convoluted histories end. Surrounding this central figure are more surreal images: a woman lies dead, a hollow man is consumed by darkness, a lumad child devours a hamburger, while white-clad diwatas seduce us in a grove. The language of this landscape evokes an experience of the real with the texture of a dream following illogical associations as they appear in the canvas. Crowning this composition is a symmetrical configuration of a Naga (indigenous dragon) okir design and a Chinese-style dragon facing each other, mirroring, or perhaps confronting each other – the local meeting the global imagineries. One wonders whether these are deliriums of madmen or our own monologues that question our present individual and societal conditions.

The second panel then is awareness – it speaks of the here and now, the present realities formed by the actions of the past, leading our senses and imaginations to the depressing anticipation of the not yet.

The exhibit is open from October 11-25, 2019 at the Rodriguez Hall, Ateneo de Davao University Jacinto Campus.

By Vinci Bueza