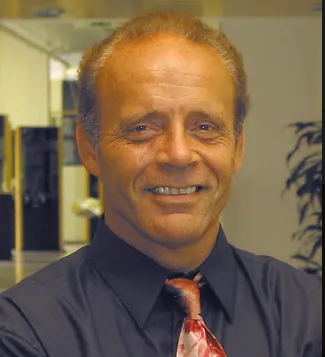

BY DAN STEINBOCK

BY DAN STEINBOCK

ON THURSDAY, the Philippines saw hours of political drama that left masses of Filipinos angry and ICC observers perplexed. The Duterte rendition could have long-lasting, adverse consequences in both the Philippines and the ICC.

In the Senate’s much-anticipated Duterte detention hearing on Thursday, Senator Imee Marcos, chair of the Foreign Affairs Committee, interviewed the key cabinet members of President Ferdinand Marcos Jr., her brother. One by one, Marcos contrasted their responses with prior interviews, ICC and Interpol documents, highlighting deep gaps between official statements and actual realities.

In a telling moment, Secretary of Interior Jonvic Remulla said the government did not “plot” Duterte’s arrest prior to March 11. Then, Senator Marcos showed Remulla’s prior TV interview in which the minister acknowledged that he, the president, Defense Secretary Gilberto Teodoro Jr., and Security Adviser Eduardo Año set the arrest of Duterte in motion.

Troubling inconsistencies

Secretary Año said the claims that he, along with the president, Justice Secretary Crispin Remulla, and Defense Secretary Gilbert Teodoro, had conspired to plan Duterte’s arrest were untrue. He was unaware of any coordination with the ICC and learned of the Interpol notice on March 11. Yet, Marcos cited Interpol’s communication, stating the arrest was made “with prior consultation with the Philippine government.”

Año also said that any meeting regarding this matter occurred only after they were made aware of Interpol’s “red notice” for the former president’s arrest. Yet, the country’s transnational crime (PCTC) director, Anthony Alcantara, admitted that Interpol did not issue a red notice against Duterte, only a diffusion notice; that is, not a notice needed to undertake a provisional arrest, but a lower-level alert for information sharing.

Justice Secretary Remulla contradicted his 2024 statement under oath before another Senate hearing that any ICC arrest order or Interpol notice should be brought before local courts. Instead, Duterte was pushed forcefully into, oddly, a private plane by Police Maj. Gen. Nicolas Torre III after Duterte’s lawyer was handcuffed.

Vice President Sara Duterte said her father, former President Rodrigo Duterte, was taken into custody “without a valid warrant issued by a Philippine court, without due process.” The ICC is being used for political persecution “to demolish the opposition” prior to the 2025 and 2028 elections.

As legal scholar Alexis F. Medina concluded in his prior opinion and during the hearing, the arrest of the former president raises “several critical constitutional concerns – due process, warrantless arrests, and liberty of abode, among others.”

During the weekend, Sen. Imee Marcos said that she hasn’t had a conversation with her brother, President Marcos Jr., in a long time.

The ICC’s original compromise

In the 1990s, the special tribunals established by the UN Security Council to prosecute crimes in the Balkans and Rwanda fostered efforts to create a permanent court. The International Criminal Court (ICC) was the international community’s response to renewed atrocities and ethnic conflict. But it was constrained at birth.

In the 1998 Rome Conference, the scope of the court’s jurisdiction was one of the most intensely debated topics. Many NGOs and rights organizations advocated universal jurisdiction. By contrast, the United States and some of its allies advocated jurisdiction based on UN Security Council authorization.

In the subsequent compromise between the idealists and the realists, the ICC would have jurisdiction over alleged crimes committed on the territory of a member state, by the national of a member state, or in other situations when the Security Council has authorized court action.

This compromise allows the court to investigate and prosecute the nationals of a non-member state; as in the case of the Philippines.

Allegations of partiality: Kenya, Uhuru, and ICC

Cognizant of its limitations, the ICC began its operations cautiously in 2003. It moved ahead only when the country in question had requested court intervention (Congo DR, Central African Republic, Uganda) or when the UN Security Council had authorized the role of the court.

Despite increasing international divides in the early 2010s, the ICC’s pattern changed when its prosecutor launched its first investigation without explicit state support against President Uhuru Kenyatta (who eventually beat the case). In the messy case involving lucrative external interests, the line between legitimate prosecution and political persecution grew thin.

Many African nations regard the court, which has largely focused only on the poor, resource-rich countries of Africa, as a “toy of declining imperial powers.”

Yet, the ICC didn’t take a step back. Its ambitious prosecutors ignored caution when engaging in investigations, which brought the court into direct contests with several non-member states, including Russia, Libya, Myanmar, the U.S. in Afghanistan, and more recently, Israel in Gaza. The results were predictable.

In two decades, the prosecutor has secured convictions in only 4 cases, typically in cases against citizens of member countries. Cases against non-member state nationals have yielded almost nothing.

Rising tensions

Oddly, the role of Martin Romualdez, the Speaker of the House of Representatives, in the ongoing dynastic debacles has been largely excluded in international media, even though in domestic debate, it is seen as vital to the turmoil.

Moreover, the Marcos/Duterte debacle is characterized as a battle of “two political dynasties.” Yet, the Dutertes have neither the economic resources nor the links of President Marcos Jr with the financial elites. After his victory, the president convened some of the country’s “boldest business minds” to “strengthen synergies” between the private and public sectors. To Marcos’ champions, the “billionaire club’s” role is only advisory. To Duterte supporters, it is reminiscent of Marcos Sr’s cronies.

Furthermore, the government’s mounting debacles – murky budget items and eroding economy, outsourcing of military sovereignty to rotational US bases, and perceived illicit measures in Duterte’s expulsion – have stirred growing resentment among the populace.

The government insists it is only observing international pressures. Yet, critics argue that some cabinet members have violated the Philippine constitution and its Cooperation Agreement with the ICC. The ICC observers fear its procedures may have been undermined.

Given the present course, the 2010s Uhuru/ICC pattern – domestic political rivalry offshored to the ICC, uncertainty in domestic economy, detrimental geopolitics, and weaker economic prospects – may now be evolving in the Philippines.

——————————————————————————————–

Dr. Dan Steinbock is an internationally recognized strategist of the multipolar world and the founder of Difference Group. He has served at the India, China and America Institute (USA), Shanghai Institutes for International Studies (China) and the EU Center (Singapore). For more, see https://www.differencegroup.net