Below the hills of Migdayas and Binaton lay the village of Melilla and Saliducon. The west and south of Melilla were hemmed by lush forest but on its eastern side, the land gently sloped down to what is now the national highway that rushed past Tuban and unto the sea village of Lub-bo.

Long before the Americans came all villages around Lubo or what is now presently known as Sta. Cruz in Davao del Sur were owned by the Bagobos of the Bawa tribe. At night, you hear the distant haunting music of the “tang-gong-go” played on eight brass agongs of different sizes. They were hanged in ropes on a sturdy wood at different heights creating different pitches. The sound echoed through the villages. Every once in a while,the rhythmic thudding of the “gimbar” or drums and the deep even tones of the “bandir” the biggest agong , were all that can be heard. The musician left his agongs and was dancing to the rhythm of the gimbar and bandir. Then he beats each agong ever gently, one agong at a time, then started playing again the tang-gong-go.On a silent night, there can never be a more plaintive sound than that of distant agongs.

In the late 1800,there lived in Saliducon an elderly couple, Bawag and Igom. One of their daughters was named Oleng. She was dark but pretty. As expected, she could bring a rather rich “sablag” (dowry) to the old couple. She was after all a daughter of a datu.

Down in Lu-bo, close to the sea lived another young married datu. His name was Eteng. He owned most of the land at the mouth of Pilan Creek and most of what comprised the village. Years later, an American, Mr. Gunn, traded all of the lands for a few horses.

Eteng spent his time going from one neighboring village to another astride his favorite “kuda” or horse to do some “balikwat” (business swapping or trading) or to do “magaliyog” (collecting).However, there were also days when he had to attend traditional feasts.

After the rice harvest, there was the “anig” where the first ceremonial eating of the year’s harvest was done. Later came the “pakat karo,” the blessing of the farm tools. But the most important was the “inyuman” to celebrate some past victory in tribal wars. Inspite of the rules laid by the Spanish government the Bagobos somehow managed to dance the sacrificial dance. The “elang” (slave) was brought forward, naked and tied to a stake. He was thoroughly but lightly beaten from head to foot with the “darodo” whose small red flowers stained the victim red. At a given signal, the Chief of the village let out a large whoop and strike the first and most fatal blow. Then the lesser warriors joined the orgy, their flashing kampilans stained red but not by the darodo.

During Eteng’s later years,the “inyuman”became a ritual drinking of the “balaba” (sugar cane wine) and an annual commemoration of old feasts and traditions. The American regime in its early years, placed the custom under strict surveillance. Thus, if any “elang”was to be sacrificed, it was done secretly. Openly “the inyuman” was a nine-day affair. On the last day, food was served and dancing lasted a day and night. Into the village came all the young warriors and maidens. They came with their “kurong kurongs”

jingling from their wrists, necks, waists and ankles. The young warriors were resplendant in their brightly tassled beaded “totob” (headress) and “kabir.” The older ones wore the saucer like “pamarang” (earrings) made of ivory.

Some male guests were set apart though and got their due respect by the headdress they wore, a reddish brown white dotted cloth. None dare touch the “tankolo” (special headdress). It proclaimed to all that the warrior has killed many slaves and enemies.

The maidens were just as colorful. They wore their shiny “panapisan” (abaca woven skirts) paired with a richly beaded “empak” or blouse and carried gay “kambols” or bags. Their rich “saloboy” hung from their shoulder down to the opposite hips. Their “lolins” (headdress) waved gaily made from hair of wild boar or kuda with tassels fastened to a wooden comb. The daughters and wives of the datus were better dressed. Around their necks were “kamagis” made of pure gold which can cost a datu several horses and agongs. Among those who came to this particular feast was the young Oleng.

In and out and around the agong players, the maidens danced in groups. Sometimes, older dancers would stretch their arms and join the younger ones dancing the “darimora” imitating the brown and white hawk that circled the skies not beating their wings for some breath taking moments.

Suddenly, there was a whoop and an eager cry. The giggling maidens ran to the side to give way to two young warriors, each with a “kalasag” (shield) but one armed with a kampilan (bolo) and the other with a “pangido” (spear).They crouched menacingly, facing each other. Only the “bandir” and “gimbar” can be heard in a savage rhythm. This was the “paligese,” a war dance and the onlookers egged the two warriors on with loud “pagayes” (war whoops).And just as suddenly, with a final lunge, the two “maganis” (brave ones) left the dance circle.

A week later, Eteng went up to Saliducon. He has seen the dark and comely Oleng at the Inyuman.With his go betweens ,he was on his way to her house. At the “kagon” (bride asking), his go betweens asked for her hands .The shrewd Bawag appraised the young but already married Datu.He was agreeable but can he afford the sablag?He then demanded for five horses, three carabaos, five “dango” (a measurement of the tip of outstretched thumb and pointing finger) of kamagi,huge plates and bowls from China, two male and female “katakyas” or brass beetle nut holders with two young slaves into the bargain.

Oleng was Eteng’s second wife.The third was Ebe.The first wife was referred as “duma” (real wife).All other wives after her were called “dowes”.They and their offsprings occupy a lower status in the family circle.They did the heavier share of household chores such as pounding of rice, digging of camotes and fetching water and firewood. But not Oleng, although a “dowe”,she was a datu’s daughter. The first wife was a commoner. Besides,she was young.

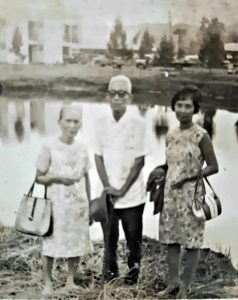

From their union were born three daughters- Oyog, Onme and Tomasa. Oyog was my paternal grandmother.

In 1912, an industrious young man named Agol, son of the Palad and Ontas came to Tugbok from Sinuron,Sta Cruz ,Davao del Sur (see the book Industrious Men by Justice Villamor). He worked as a farm laborer of Saito,a Japanese settler.He saved some money and made friends with the Bagobo Guiangans. From them, he bought or bartered many hectares of land . Later,in a celebrated court case against the government, Datu Angalan testified in court how Agol acquired the properties (Supreme Court archive).By 1915,he owned 350 hectares of land in Subasta and Balingaeng, Davao City. In his time,he was well known in political circles as a leader.Among his friends were the older Generoso, Jaymes, Chavez,Inigos and the Bastidas.He was then married to Oyog, one of the daughters of Eteng.

Later, the children came – Inding, Olo, Oska and Oning. Olo or Fructouso Palad Sr. was my father.

Meanwhile, in Hindang, Leyte lived a couple- Catalino and Catalina Ballerda. Their youngest son was Filomeno. Although born of very pious Catholic parents,he decided to join a travelling pastor, Leocadio Carino and promptly became a Protestant convert. He remembered being stoned and spitted on by his listeners and suffered from his family’s and townmates’ displeasure. They made fun of him for reading the Bible, praying with closed eyes and for preaching.

Born poor, he somehow managed to reach Dumaguete and enrolled at the well known Protestant institution Silliman. Mama said he worked as a waiter in the dormitories while an aunt claimed he was tasked to light the lamps of the school but my guess was , he did what the Americans assigned him to do.

After finishing the seventh grade, the determined Filomeno volunteered to work among the natives of Davao as a teacher missionary. He was assigned to the Bagobo village of Melilla in Sta Cruz. After a year,he went back to Leyte where the reception was warmer .This time, he was a maestro.He then went to Butuan to teach in a public school.

At the mouth of the Agusan River is Butuan , where a German American Carl Wantz lived in 1916.He was engaged in a water transportation business .With him lived his step daughter, Carmen and his own son,William.

After studying in Cebu with the nuns, Carmen went back to Butuan and became a public school teacher at nearby Buenavista. There she met the young Filomeno with whom she fell in love. Better the muchacho than that maestro, her stepfather shouted. They then decided to elope and headed for Melilla,Sta Cruz to work with the American Board Mission at the Robert Black Memorial School. They worked under the Rev Julius Augur who lived at Madapo Hill near Brokenshire Memorial Hospital. They and their 10 children lived with the Bagobos. The children were required to speak English but were also fluent in the Bagobo dialect.

The couple’s second child was Elizabeth, my beloved mother. Once in a while,she was brought to the city to watch over the children of Pastor Augur.

Mama and Papa met in Idong,Sta Cruz in 1938 where my mother was then teaching in another mission school. Papa was visiting his stepmother.

Today, we live in a 50 hectare property inherited by my father from Lolo Agol. From our mother, we learned to treat and love as equal the families working in our land and to share whatever bounties God has given us. From our Bagobo father, we learn to work so we may live and to lòok upon the farm as God given and life sustaining.

Today, Lub-bo the village once ruled by Datu Eteng is now a thriving town of Sta Cruz whose income depends largely upon ifs fishermen living in Sibule and Apo Beach and the coconut plantations owned a few of its old families. Should you visit the town,you will see that one of its streets honor my great grandfather- Calle Datu Eteng.

(Author’s Note: This was a collaboration between me and my dearest mother many, many years ago. She provided all the details of the story. Later, I studied in Silliman and learned to write on my own but as you can see, my mother has a big influence on my style of writing. But I also thank Prof. Chanco.”You write to communicate and not to impress so use simple words as much as possible. Write, as if you are narrating a story,” the good professor reminds us in our Feature Writing class.)

By Susan Palad