Philippine elections are cultural extravaganzas. They have the same energy as our colorful festivals and fiestas. And they are more expensive and more time-consuming than all of our local and national celebrations combined.

During electoral campaign season, our Filipino creativity is in full display and our deep-seated cultural norms and beliefs are affirmed.

We get to see the most clever slogans and hilarious puns; the most catchy campaign jingles designed to give us last song syndrome (LSS); the most brilliant candidate makeovers and profile photos polished by artificial intelligence (AI).

This is the period of boom in our creative industries. I do not know if that is the reason why they start the national campaign period during the celebration of National Arts Month.

We also tap into our Filipino cultural traditions like “utang na loob” (debt of gratitude) and close family ties and practice them like extreme sports during elections.

That is why “ayuda” is a buzzword here in the Philippines because it is vital to the patron-client relationship. It reinforces the “utang na loob.” It is reciprocity on steroids.

The prevalence of political dynasties is the extreme manifestation of the concept of kinship – networks that grew out of blood relations and marriage. Philippine politics has become a major industry and it is mostly composed of family corporations. In fact, elective positions have become included in the inheritance. This gave rise to the phenomenon called “bimpo” or “batang isinubo ng magulang sa pulitika” (children forced by their parents into politics). The nepo babies.

These family enterprises engage in vote buying as an “investment,” which they will recoup once elected through various creative schemes. Oftentimes they will have investors to bankroll their campaign and these investors get their return through lucrative contracts in “development” projects. The development of the politician and the investor, that is.

The electorate justify accepting the “ayuda” and selling their votes as their share in “development” since the politicians’ projects will not benefit them anyway. Thus, they rationalize that elections are the only time they get their share of the pie.

When citizens distrust electoral institutions, they may view vote buying as a practical way to extract immediate benefits from a flawed system. In cultures where corruption is normalized, voters may not see anything wrong with accepting money in exchange for their votes.

In societies where patronage systems dominate, politics operates though personal relationships rather than institutional integrity. Voters expect material benefits from politicians jn exchange for electoral support. This culture fosters an environment where political loyalty is transactional rather than ideological.

In the Philippines, voting is often a collective decision influenced by family and community leaders. If a leader negotiates benefits from a politician, individuals may feel obligated to comply, reinforcing the vote-buying culture.

The electoral campaign is also “That’s Entertainment” and “It’s Showtime” combined. That’s probably why showbiz personalities perform better in surveys and in getting the votes. In thjs country, if you want to be elected into office, you have to make it as an entertainer first.

Even serious politicians now make efforts to entertain us during legislative hearings like they are auditioning for a reality show. Life imitating art and all that.

When leaders are elected based on popularity rather than competence or policy expertise, it reveals significant cultural attributes about a society.

A culture that prioritizes entertainment and social influence over policy expertise may be more susceptible to electing charismatic figures with broad media appeal rather than qualified leaders with governance expertise.

A culture that emphasizes personality over policy will have voters who may prioritize a candidate’s image, likability, and rhetoric over substantial political agenda.

When institutional credibility is low, people may be drawn to well-known figures who appear relatable or independent, rather than experienced politicians perceived as part of the corrupt system,

A culture that values short-term gratification and instant results may lean toward leaders who offer quick-fix solutions or compelling narratives rather than long-term sustainable policies.

When emotional appeal outweighs rational evaluation in electoral decisions, it suggests a political culture shaped more by sentiment and spectacle than by evidence-based policy analysis.

Culture js an invisible yet powerful force that shapes elections in various ways. It influences voter behavior, political strategies, and the overall electoral landscape.

By understanding cultural dynamics, good leaders can engage more effectively with voters, ensuring that democratic processes reflect the values and aspirations of the people they serve.

Right now it is the cunning and media-savvy politicians who use their understanding of Filipino culture to manipulate and exploit voters to their advantage.

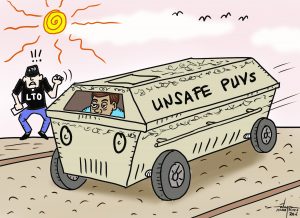

Addressing the cultural factors that contribute to vote buying and popularity-driven elections requires long-term efforts, including voter education, stronger democratic institutions, and economic reforms to reduce dependence on electoral handouts and media-driven political campaigns.

By understanding how elections work in our country, we also learn about ourselves as a people. Sadly, it tells us a sad story of our distorted notion of democracy.