I am the primary caregiver of two loved ones — my 84-year old mother who is living with lupus and my 54-year old spouse who is recovering from a stroke and is also in dialysis three times a week for four years now. You can imagine the financial, physical, and emotional costs we deal with on a daily basis.

I am the primary caregiver of two loved ones — my 84-year old mother who is living with lupus and my 54-year old spouse who is recovering from a stroke and is also in dialysis three times a week for four years now. You can imagine the financial, physical, and emotional costs we deal with on a daily basis.

It is fair to say that I interact with what passes off as our health care system every single day — before, during, and after the height of the pandemic. I am sad to report that, despite advances in technology and countless congressional committee hearings in aid of legislation on how we can make things better, the state of our health care system is still as bad as it was and getting worse.

In a study made by Vincent Gregory Yu of the Ateneo de Manila University Development Studies Program, he described the health financing experiences of ordinary Filipinos as 4Ps — “pagtitiis, pangungutang, pagmamakaawa, and Philhealth.”

According to data from the Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA), the poorest Filipinos spent a total of P190.43 billion or 17.5 percent of total health spending in the country in 2021. And that’s just the poor.

The Current Health Expenditure (CHE), which is the country’s total health expenditure, reached P1.09 trillion in 2021. About 50 percent of that or P546.64 billion went to government financial support for Filipinos in need of medical assistance.

Meanwhile, the “out-of-pocket” expenses of health for Filipino households amounted to P451 billion or 41.5 percent. That is still a lot, even with government assistance.

And the number is only increasing through the years. More and more Filipino families face what they call “catastrophic health expenditures,” which are greater than or equal to 40 percent of a household’s capacity to pay.

I remember then Mayor Rodrigo R. Duterte telling me that Filipinos do not die of diseases, they die because they cannot afford the high cost of health care in the Philippines. Because many of the diseases can still be cured if you have enough money to pay for treatment.

That is why the first P of Yu’s 4Ps is “pagtitiis.” Most Filipinos would rather endure the symptoms of their health conditions, refusing to seek treatment and resorting to self-medication.

So most chronic diseases like cancer get diagnosed at later stages of the disease because of this “pagtitiis.” Oncologists have invented a term, “financial toxicity,” as another factor to consider along with biochemical toxicity in deciding on the appropriate treatment for their cancer patients.

David Cutler, in an article published in Harvard Magazine in May-June 2020, wrote that the United States has the “world’s costliest health care.” And the American public think it is because of “unconstrained greed” with “pharmaceutical companies putting profits above patients and insurance executives paid millions to deny coverage.”

I cite the US as an example because the Philippines likes to follow the American way, including how we run our health care system. True enough, as I read through the article, I noted that we share the same problems.

Beyond greed, there are other factors involved why health care costs a lot. Cutler named three in his article.

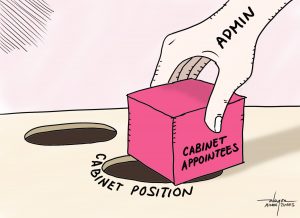

First is the high cost of healthcare administration. I do not understand why we cannot follow just one standard system for all hospitals and all government agencies. Why can we make online banking work and can even pay bills through our mobile phones but it takes forever to process our hospital bills?

There is an entire section that handles admission, then there’s another just for Philhealth, then another for billing, another for government assistance, another for social services, then the cashier, and on and on. It is easier to order several things online and have them delivered all the way from China spending just a few minutes with a few clicks on your phone than transact payment for your hospital bill for one patient.

This system costs a lot to maintain and it is not working. It is stressful to the patient and taxpayer and their families and it is difficult to manage for the government. And don’t get me started about the Philhealth computer system bogging down almost every other day. Government must seriously invest in a system that works for all. An efficient and effective system will save us money in the long run.

Second factor is price gouging. Why are the same brand of medicines more expensive in the Philippines than in Thailand or India? And it’s not just Big Pharma that’s gouging the prices, hospitals do it, too.

Hospitals here in the Philippines are run like hotels. The cost of your procedure, medication, laboratory, and even doctors’ professional fees are based on the kind of room you are staying in. The higher the price of the room per night, the higher the price of the service.

Why would the X-ray or paracetamol cost vary depending on what room you are in? Is the X-ray result printed in color when you stay in a suite room? Will the paracetamol come in a different flavor if you are in a deluxe room and it will be just plain if you are staying in a ward?

Maybe it is not just the price of rice and other basic commodities that should be fixed and regulated by the government, but medicines and medical services, too. After all, health is a basic human right.

Third factor cited is the misallocation of medical resources. More investments should be made in primary care and disease prevention. Maybe the solution to increasing incidence of cancer is not building more cancer hospitals to treat cancer patients but more nutrition education and healthy lifestyle promotion to prevent cancer from happening in the first place.

It has been often said, prevention is better than cure. Let’s allocate more on health education and promoting access to affordable healthy food in schools and communities. Our food security program must be tied to our health and education programs. That’s how we assure that we will have high levels of human capital.

Let’s create the new 4Ps in healthcare — prevention of diseases, production of nutritious food, price regulation, and people-centered system.