By Herman M. Lagon

IF POLITICS were a school subject, the word “Trapo” would have been one of my first unforgettable vocabulary terms. I first heard it in a college class on Philippine governance in the early 1990s, scribbled on the board as shorthand for “traditional politician.” It sounded almost innocent—a mere acronym, something you could easily memorize for the midterm exam. But then came Yano. Their raw and raging anthem, “Trapo,” blasted from campus cassette players and protest caravans, its lyrics gritty, unfiltered, unforgiving. Suddenly, Trapo was not just a word; it was a worldview. I began to notice it everywhere—in student council meetings, during solidarity marches, in AM radio punditry. What was once a classroom term had transformed into a cultural red flag. When I learned early on that it also fitly meant “rag”—dirty, worn out, something to be thrown away—it hit even harder. The word was not simply descriptive; it was prophetic.

The real sting of the term came when I saw how close it was to the truth. Trapo politicians wielded recycled promises like campaign flyers. They wept on cue, kissed infants for the camera, and rolled out medical missions that doubled as re-election strategies. They mastered the choreography of charity, while their backrooms reeked of patronage, corruption, and ambition disguised as concern. This was not a mere coincidence. The sociopolitical fabric they thrived in, woven from utang na loob, pakikisama, and palakasan, had kept them untouchable for decades. It was jarring how one short word—five letters, two syllables—could carry that much rot.

Now, in 2025, after another cycle of midterm elections, I find myself wondering if Trapo still captures the political moment. The answer, unfortunately, is yes. The word has aged but not expired. It has evolved like its subjects. Today’s Trapo no longer just rides in parades with big hair and velvet sashes. He posts TikToks of himself feeding stray dogs, silly dancing for good vibes, launches “scholarship funds” sourced from public coffers, and joins webinars to talk about empathy and sustainability—as if they were not part of the system that made empathy and sustainability so elusive in the first place.

Some have gone digital, even AI-savvy. They hire ghostwriters for their posts, deepfake smiley town hall videos, and seed praise campaigns through bots and trolls. But peel back the polish, and the pattern is the same. The soundbites have been rebranded, the hashtags upgraded, but the governing philosophy—if it can even be called that—remains rooted in illusion, familiarity, and expediency. As detailed in studies by the Ateneo School of Government, dynastic candidates still dominate over 80 percent of legislative seats, proving that name and face matter more than bills passed or debates won.

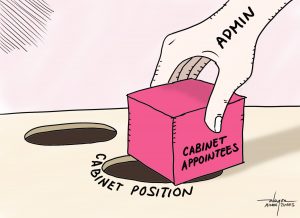

What makes Trapo a sticky descriptor is not just the gimmicks, but the posture. It is how one performs politics like theater, confusing noise for vision, name recall for integrity, and attention for credibility. The Trapo is performative by design. He waves from tinted SUVs, cuts ribbons with exaggerated grins, funds birthday parties of barangay captains, and builds halfway-finished basketball courts a week before elections. And when caught in scandals? He blames the opposition, feigns memory lapses, or tearfully reads a legal statement while flanked by his family, who just so happen to be running too.

Yet despite all these, many of them win. Again. And again. It would be tempting to pin the blame on voters. But that would be too neat. The reasons are layered: institutional failures, poverty, patronage culture, disinformation, and a citizenry long trained to equate aid with love. As noted in the 2023 SWS survey, 41 percent of voters still identify “being helpful to the poor” as the strongest sign of good governance, a metric that is emotional, not empirical. That is not ignorance; it is survival logic in a system that has repeatedly failed its people.

What worries me is how the term might adapt. In the future, the Trapo might wear barong still, but also quote philosopher and political theorist Hannah Arendt in campaign speeches. He might retweet feminist manifestos, raise rainbow flags during Pride Month, and advocate mental health awareness—only to later gut education budgets, silence student protests, and keep laws vague to preserve control. He may look woke, but governs like a dictator. That would be the most dangerous version: a progressive on the outside, a patron on the inside.

But amid this cautionary tale, I remain hopeful. If anything, the last midterm elections have taught us that change, while slow and bruising, is not impossible. The rise of volunteer-driven campaigns, fact-checking collectives, and youth-led movements proves that we are not entirely captured. In 2022 and 2025, we saw voters lining up at sunrise, refusing payoffs, and attending house-to-house campaigns led by unpaid students. Even Yano’s “Trapo” was sung anew, no longer just a lament but a protest soundtrack re-energized by a new generation.

We must nurture that spark. But doing so demands more than memes or moral superiority. It requires supporting platforms, not personalities. It means listening even to those who vote differently, not to correct them, but to understand the survival strategies that inform their choices. It involves running for office, mentoring future leaders, or simply showing up in local meetings where contextual decisions often matter more than national ones. And it definitely means naming the Trapo when we see him, not just during elections, but long after the tarpaulins are taken down.

The word Trapo, at its core, is a cultural mirror. It forces us to ask not just who they are, but who we are. What do we celebrate? What do we forgive? What patterns do we perpetuate by silence, by cynicism, or by forgetfulness? The midterm elections may be over, but the story of the Trapo is not. He is still among us, smiling in posters, trending online, shaking hands, and taking oaths.

And yet, maybe there is hope in those willing to flip the script—who treat public service as a duty, not a show. They call out the mess and dare to clean it up. It is never easy, but real change begins with telling things as they are.

***

(Doc H fondly describes himself as a “student of and for life” who, like many others, aspires to a life-giving and why-driven world grounded in social justice and the pursuit of happiness. His views do not necessarily reflect those of the institutions he is employed by or connected with.)