Dr Dan Steinbock

Dr Dan Steinbock

AT THE height of the COVID-19 pandemic, the US military launched a secret campaign to discredit China’s Sinovac inoculation and to counter what it perceived as China’s growing influence in the Philippines, according to a new Reuters investigation.

The clandestine operation hit the Philippines, which had been hit particularly hard by the virus. I should know. I was in Metro Manila at the time.

In 2020, I released two reports on the pandemic and its international human and economic costs. The situation was dire in the Philippines.

I took the Sinovac shot twice and talked with some who were afraid to do so and chose to wait. Since then, I have wondered what happened to them.

US troll farms against Chinese Sinovac

The covert US military operation was particularly harmful because, as Reuters put it, “it aimed to sow doubt about the safety and efficacy of vaccines and other life-saving aid that was being supplied by China.”

How did it happen? Fake internet accounts impersonating Filipinos and used by the US military’s propaganda were transformed into an anti-vax campaign. As Filipino public health officials struggled to contain the epidemic, the covert operation morphed social media posts into troll farms, decrying the quality of face masks, test kits, and especially the first vaccine that would become available in the Philippines — China’s Sinovac inoculation.

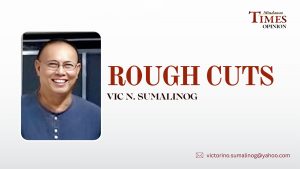

Reuters identified 300 accounts on X (formerly Twitter) matching descriptions shared by former US military officials familiar with the Philippines operation. They urged Filipinos “not to trust the China vax, which was a “rat killer” and so on. (See Figure 1)

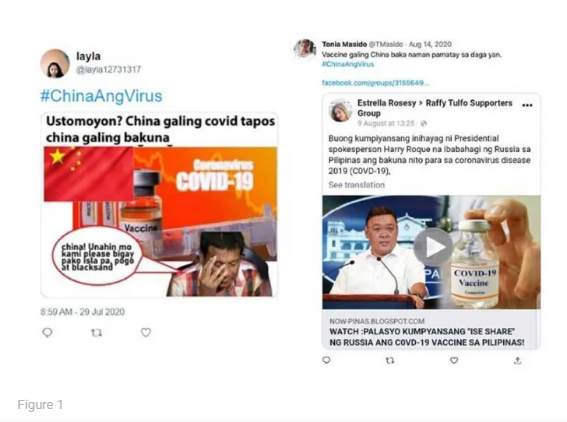

The origins of the US operation went back to the pre-pandemic 2019, when Trump’s defense secretary Mark Esper signed a secret order paving the way for the launch of the campaign. As Pentagon’s “competition” with China was identified with “active combat,” it enabled the military to bypass the State Department in its psychological warfare (psyop) operations. Ironically, that year, Esper was shaking hands in the Philippines with his counterpart Delfin Lorenzana, a meeting that was later linked with pledges of quick vax delivery and military cooperation, as reflected by a Rappler report. (See Figure 2)

From PH and Southeast Asia to Central Asia and the Middle East

Pentagon’s active use of social media tools began around 2010, with the onset of the Obama “Pivot to Asia,” “leveraging phony accounts to spread messages of sympathetic local voices — themselves often secretly paid by the United States government.” Today, the US military employs an extensive ecosystem of social media influencers, fronts and covertly placed digital ads to influence overseas audiences. In the Philippines, these ops are fostering an atmosphere of fear and political paranoia.

Most social media accounts were created in the summer of 2020 and centered on the slogan #Chinaangvirus. The anti-vax effort started in the spring of 2020, expanding beyond Southeast Asia before it was terminated in mid-2021. Some of the set of fake social media accounts used by the US military “were active for more than five years,” according to Reuters.

After the successful test run in the Philippines and Southeast Asia, the clandestine propaganda campaign was tailored to and recycled among local audiences across Central Asia and the Middle East. It was designed to spread fear of China’s vaccines among Muslims when the virus was killing tens of thousands of people daily.

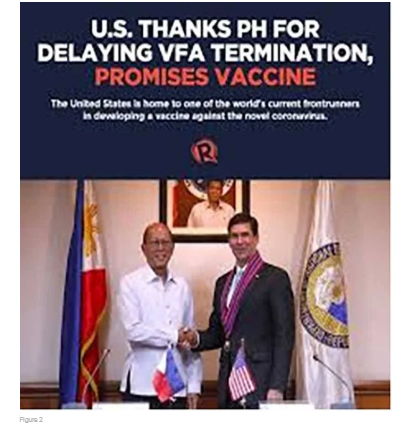

But why was the timing so destructive in the Philippines? Two (linear-scale) charts tell the story. When the US military anti-vax operation kicked in, there were fewer than 20,000 detected cases in the country. In the next three months, that figure surged to 215,000, and by the end of the year, it exceeded 460,000, soaring to 2.8 million by the year-end of 2021. In mid-2021, the Philippines still had one of the worst inoculation rates in Southeast Asia. The difficulty in vaccinating the population, thanks in part to the covert US military op, contributed to the worst death rate in the region. (See Figure 3)

Attack undermined global vax supply

The US campaign undermined the supply of life-saving vacs when they were needed the most. In May 2020, Chinese President Xi Jinping said the Chinese vaccine would be made available as a “global public good” to ensure “vaccine accessibility and affordability in developing countries.” Sinovac was the primary vaccine available in the Philippines for a year until US-made and other vaccines became more available in early 2022.

Running the program through the military’s psyop center in Tampa, Florida, the US military disregarded the collateral devastation the propaganda was expected to have on Filipinos. “We weren’t looking at this from a public health perspective,” said a senior military officer to Reuters. “We were looking at how we could drag China through the mud.”

Worse, Washington’s own vax plan inoculated Americans first and placed no restrictions on what Big Pharma could charge developing countries for the remaining vaccines. It let the US pharma giants “play hardball” with developing countries and suck the supply out of the global market. It set a terrible precedent for the West’s vaccine nationalism at the expense of human lives in the Global South.

They knew

Who was in charge? The campaign began under former president Trump and continued months into Joe Biden’s presidency. Worse, it prevailed “even after alarmed social media executives warned the Biden administration that the Pentagon had been trafficking in COVID misinformation,” as Reuters found.

Knowing the lethal implications of the campaign in several world regions, Facebook could have protested. It didn’t. There could have been resignations. There weren’t. What about orchestrated leaks? None. In the past, opposition from the State Department might have penalized the program. Not so now.

To implement its anti-vax campaign, the Pentagon overrode objections from top US diplomats in Southeast Asia. Yet, during the Gaza war, many patriotic Americans in the US military, intelligence, and foreign service have protested the genocidal atrocities, and some have resigned. Not so in the Philippines. There was no public protest by US Ambassador Sung Y. Kim or his successors, John C. Law and Heather Variava, from early 2020 to mid-2022, not to mention resignations. And so, Jonathan Braga, senior US military commander responsible for Southeast Asia, could target Sinovac, and the campaign was expanded to target Muslim-majority countries.

Following an audit of its campaign, the Pentagon criticized its primary contractor, General Dynamics IT, for getting caught due to its sloppy tradecraft and inadequate steps to hide the origin of the fake accounts. But there is a silver lining. In February, GD won a $493 million contract to continue providing clandestine influence services for the military. These are the kind of defense contractors that also play a role in the Philippine’s weapons buys.

Thanks to its weapons sales in Ukraine and Gaza, GD stock has almost rippled up to $300 since early 2020. But new conflicts will be needed in Asia to sustain the stock surge in the future. It’s just business. (See Figure 4)

Dr. Dan Steinbock is the founder of Difference Group and has served at the India, China and America Institute (US), Shanghai Institute for International Studies (China) and the EU Center (Singapore). For more, see https://www.differencegroup.net/