BY DAN STEINBOCK

BY DAN STEINBOCK

WITH THE deportation of former President Duterte, the Philippines seems to be moving toward increasing political instability and economic uncertainty.

On March 11, 2025, former Philippine president Rodrigo Duterte was arrested by the Philippine National Police and Interpol on the basis of an International Criminal Court (ICC) warrant charging him with crimes against humanity in connection with the Philippine drug war.

To Duterte’s critics, it was a day of triumph. To Duterte’s supporters, it was a day of infamy. In December 2023, President Marcos Jr vowed that his government would not cooperate with the ICC’s investigation into the previous administration’s war on drugs. As Marcos stated, “This government will not assist the ICC in any way, shape or form.” He added he would “continue to defend and assert the sovereignty of the Republic of the Philippines at all times.”

In international media, the full reversal has been commented on mainly by Duterte’s old critics and the champions of the incumbent government, in line with their political interests.

What is missing is the coverage of the drug crisis Duterte inherited from President Benigno Aquino III. It was the proliferation of drugs and associated corruption and violence that paved the way to Duterte’s landslide triumph.

Drugs, syndicates, and corruption

During the rule of President Aquino III until mid-2016, complacency with drug lords and narco-politicians went hand in hand with the rise of hundreds of thousands of addicts, particularly in urban slums and poorer regions. Prior to his presidency, Duterte warned the Philippines was at risk of becoming a narco-state pledging that his government’s fight against illegal drugs would be relentless.

In his inaugural State of the Nation Address, Duterte said that data from the Philippine Drug Enforcement Agency (PDEA) showed there had been 3 million drug addicts, which he said may have increased to 3.7 million. International media disputed some of the data. Reuters reported that half of the users favored milder drugs once a year. But that still left some “860,000 who had consumed crystal meth, or shabu, the highly addictive stimulant widely blamed by officials for high crime rates and other social ills.”

Furthermore, these numbers continued to rise. And as the leaders of the poorer Filipino barangays knew only too well, the problem was severe, pressing, and getting worse.

Due to its geographical location, international drug syndicates used the Philippines as a transit hub for the illegal drug trade. Some local syndicates and gangs were also involved in narcotics, seeking to export small amounts of illegal drugs to other countries, as Al Jazeera reported in its documentary “Filipino drug mules” in 2011.

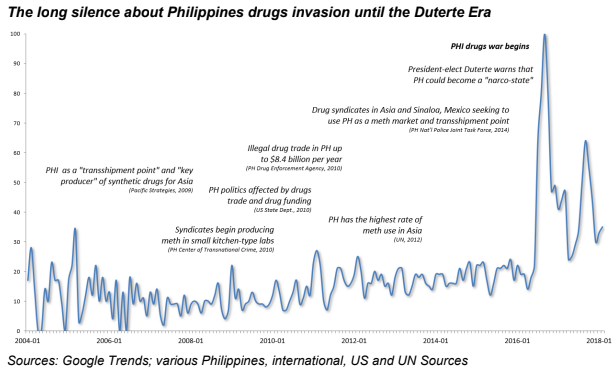

Duterte took the drug problem seriously, as did most Filipinos whose neighborhoods had been invaded by drugs for more than a decade. During the period, the drug crisis was downplayed by the mainstream media and largely ignored by international media.

There certainly were no efforts to target Philippine political and military leaders who allegedly protected the narco-bosses.

Yet, as a Google Trend search demonstrates, it was only when Duterte began the war against drugs that critics awoke, as evidenced by soaring story mentions about the Philippines and drugs in international media, mainly in the US and Europe.

Under the watch of President Aquino and his Liberal Party (LP), drug syndicates began to produce meth in kitchen labs. It caused illegal drug trade to soar to $8 billion, according to the 2010 US International Narcotics Control Strategy report. US State Department warned that drug trade and funding were affecting Philippines politics, as corruption undermined the rule of law.

Drug syndicates in Asia and Sinaloa, Mexico, saw the Philippines’ transshipment potential. But these plans were derailed. In the 2016 election, Mar Roxas, former interior minister and ex-investment banker in Wall Street, was Aquino’s designated successor, but Duterte triumphed. As a net effect, LP suffered a meltdown.

During his campaign, Duterte warned the Philippines was on the way to becoming a “narco-state,” whereas LP leaders accused him of inflating the problem. Ordinary Filipinos disagreed and voted accordingly.

Only days in the office, Duterte named five “narco-generals” believed to be protecting drug lords that allowed shabu (meth) sales to flourish during the Aquino era. Some of them had been linked with Roxas, who denied all ties with these generals.

Erosion of stability

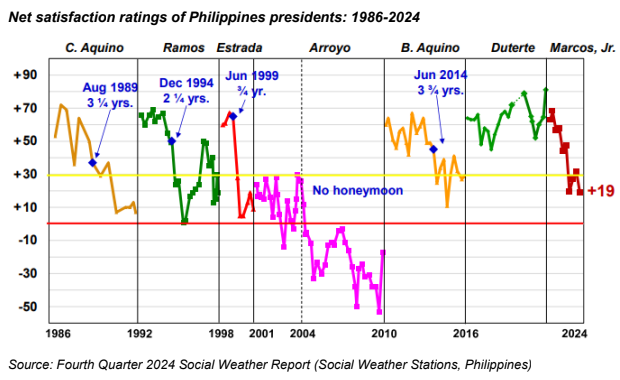

President Duterte began and ended his term with extraordinarily high ratings (80%), according to Philippines surveys). He remains very popular in the Philippines, particularly in his primary base in Davao and the south, but also across the nation. No other Philippine president since 1986 has managed to achieve equally high ratings. President Marcos’s current rating is far behind (19%) and has been falling ever since the government’s reverse course and political infighting at the expense of Filipinos’ daily economic and social concerns.

During his term, the Philippines “recalibrated” its foreign policy between the United States and China, seeking to cooperate with the former in security and fostering economic cooperation with the latter. As the promise of the Philippines as a large emerging economy was strengthened, peace and stability fostered economic growth and development. After the pandemic years, a strong recovery remained viable.

These were the objectives that the incumbent government vowed to build upon starting in 2022. But ask ordinary Filipinos today, “Are you doing better economically?” or “Are you more secure than before?” and the response is a subdued sigh or a bitter smile.

With the eclipse of the recalibration in foreign affairs, the Philippines now has more rotating foreign military bases than ever before. Despite the ongoing battle over controversial budget items, arms imports are booming. With the consequent tensions and instability, the country’s economic promise appears to be dimming.

Those Filipinos who saw Duterte as a representative of the popular masses are angry, disappointed, and feel betrayed. That’s what happens when the internal battles of the political class and their economic financiers ignore the legitimate economic and social concerns – particularly social ills – of the people.

————————————————————————————————-

Dr. Dan Steinbock is an internationally recognized strategist of the multipolar world and the founder of Difference Group. He has served at the India, China, and America Institute (USA), Shanghai Institutes for International Studies (China,) and the EU Center (Singapore). For more, see https://www.differencegroup.net .