(First of two parts)

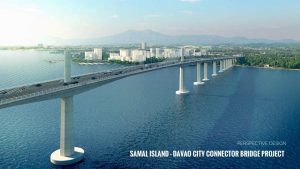

LAWYER Ramon Rodriguez Lucas, one of the owners of Coast Marina Resort on Samal Island, was visibly guarded when he sat down to discuss his family’s battle against the City of Davao over the P23-billion Samal Island-Davao City Connector (SIDC) Bridge project.

He had reason to be cautious. Along with some environmentalists, he and his cousins are fighting a lopsided battle to preserve Samal Island from an infrastructure project experts say will destroy the delicate ecosystem that made it a main tourist attraction. They are up against the local government, the Department of Public Works and Highways, and a Chinese company that was contracted despite having been blacklisted by the World Bank for short-cutting construction processes.

The local government has argued that the bridge would be a godsend, connecting the island to Davao City, currently accessible only by boat, and bringing business and development to Samal. This is why Lucas’ family, which considers itself the steward of the 400-year-old reef on the very spot where the bridge would rise, is pushing for an alternative. They are offering a different landing site for the bridge where damage to corrals will be minimized, and where sinkholes will be avoided. But their pleas have fallen on deaf ears as the meetings with the DPWH and government officials felt less of a consultation than an imposition.

“The decision was already made somewhere and we were obliged to comply,” he said. “If something happens, we don’t want to be there at the end saying, ‘I told you so.’”

Two families—Lucas and Rodriguez—own the adjoining Coast Marina and Paradise Island Park and Beach Resort. They want to save the coral reefs, an attraction that made tourism the lifeblood of Samal, with its 118 kilometers of coastline and 31 out of 46 barangays hugging the coast. Samal is relatively isolated, which explains its power woes as well as the lack of industrial and real-estate development. Public projects are also limited to road networks, government centers, and school buildings.

The family’s warning about sinkholes–along with how the calls to realign the bridge to protect the century-old corals were ignored–is emblematic of how the contractor, China Road and Bridge Corp (CRBC), government officials, and the DPWH reportedly steamrolled through the issues surrounding SIDC.

Sinkholes

The Department of Environment and Natural Resources’ Environmental Management Bureau’s 2020 environmental impact assessment (EIA) found a sinkhole “adjacent to the location of the alignment” of the P23-billion 4-kilometer Samal Bridge project.

The alignment refers to the site Samal Island where the bridge will land. A corresponding landing site has been chosen for the bridge’s opposite end in Davao City.

The EIA noted that Samal Island’s features are distinct for their geohazard risks to cavities, fissures, and sinkholes due to the dissolution of calcium carbonate and the “complex underground drainage network.”

The report said, “One sinkhole was identified adjacent to the location of the alignment. This is based on surface manifestations of a rounded depressed section presently occupied by abundant bamboo grasses.” The report went on to identify other areas along the coastline that exhibit sinkholes underneath.

Even before this, the 2015 hazard mapping assessment of the regional Mines and Geosciences Bureau listed 135 sinkholes around the island, whose limestone characteristics make it vulnerable to karst subsidence, meaning there were caves and cavities underground throughout the island, the study said.

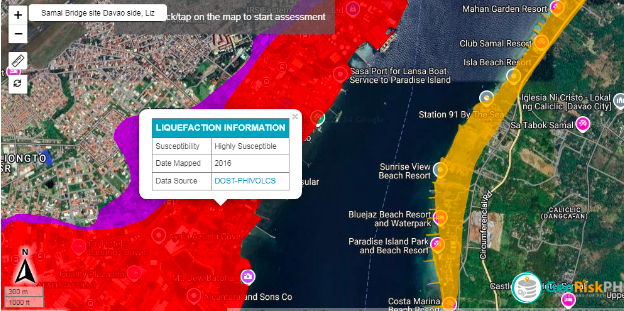

Meanwhile, on the Davao City side of the bridge, the landing site is also prone to liquefaction during earthquakes, according to Philvocs. Liquefaction occurs when the ground surface or the sediments underneath loosen due to the shaking.

Samal Island Planning and Development Office Coordinator Eleazar E. Lape said the entire island is made of limestone, which is prone to sinkholes and cave-ins due to its slightly soluble characteristics. Samal’s karst landscape indicates a network of 30 cave systems, subterranean streams, and sinkholes.

“Kung limestone area man gud, normal jud dunay mag cave-in. So, tungod kay dili siya kana bang wala man gud guidance gi include sa amoa, kung sinkholes na tanan dili na buildable (A cave-in is normal for a limestone area. But we received no guidance whether all sinkholes are no longer buildable),” he said.

Lape also recalled zero instances where a government infrastructure, road project, or even a residential area collapsed due to a sinkhole, which is why Samal Island was not declared a no-build zone. He is also optimistic the Chinese engineers performed all the necessary mitigating measures and land-scoping to ensure the bridge’s structural integrity.

“It (the sinkhole issue) is still a concern. But just like in fault lines, it’s not totally prohibited to build on a Faultline. But you need to have a setback (distance) and you need mitigating measures,” he explained.

“As much as possible, we wanted to preserve the environment,” he said. “In our Comprehensive Land Use Plan, we have a provision there that says once the bridge is finished, we will reserve urban greeneries and green spaces to control the development.”

The city is in the process of revising its 2016-2024 CLUP, which includes expanding its roads from two lanes to four lanes to absorb the additional vehicles. “We must also add bypass roads and circumferential roads but we have long prepared like our road right-of-way from the paved highway is around 20 meters,” he added.

Both the Lucas and Rodriguez families have offered their property in Barangay Caliclic at no cost to the government to save the reef. The 2016 study by Japan’s Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI) identified an old shipyard called Bridgeport as the ideal landing site considering the dead corals in the area. Finally, it would be the nearest point to Davao City, thus, resulting in a shorter and cheaper bridge.

Uphill Battle or Hopeless Cause

Environmental planner Carmela Marie Santos said the project contractor and the DPWH could afford to ignore the environmental concerns because they were enabled by the DENR, the open support of Samal City and the passivity of the Davao City local government unit.

“The city government of Samal has not been silent since it has actively and openly campaigned for the SIDC Project/China bridge,” said Santos, who is also a director of Ecoteneo, the environmental arms of the Ateneo de Davao University. “Meanwhile, Davao LGU is ‘surprisingly’ quiet in spite of what it knows and its green agenda,”

“But the ‘surprise’ is not really a ‘surprise’ if they consider this part of Duterte’s Build, Build, Build legacy—except that it has become build and destroy,” Santos said.

SIDC is one of the 75 big-ticket infrastructure projects under former President Rodrigo Duterte’s “Build, Build, Build” program and the 12 bridge projects listed in the Build, Better More program of President Ferdinand Marcos Jr.

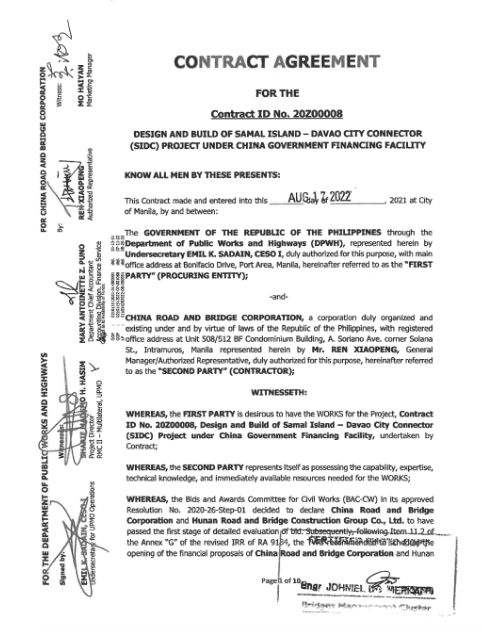

Of the total P23-Billion cost, the P19 billion will be loaned out by the Export-Import Bank of China. The framework agreement for a concessional loan was cemented on June 13, 2022, a month before Duterte stepped down as president, by then Finance Secretary Carlos P. Dominguez III and the People’s Republic of China Ambassador to the Philippines Huan Xilian.

On March 26, 2019, DPWH and project consultant Ove Arup & Partners Hong Kong Ltd presented the feasibility study to the Davao Regional Development Council, which became the basis to endorse the bridge alignment.

The contract was eventually awarded to CRBC, a subsidiary of China Communications Construction Co.

Santos said the choice of the contractor and the consultant was already a red flag. For instance, CRBC was debarred by the World Bank Integrity Vice Presidency on January 12, 2009, for a period of eight years after its investigation showed how the company reportedly shortcut several processes to bid for the first phase of the National Roads Improvement and Management Project.

CRBC’s mother company, the China Communication Construction Co., was also debarred in 2011.

Meanwhile, Ove Arup & Partners Hong Kong Ltd, the consultant tapped to prepare the SIDC Project Description Report was also a subject of controversy when the Hong Kong government suspended it for three months for conflict of interest and the use of insider information for a government housing project in Wan Chau.

“The experience with government in between has not been a walk in the park. One thinks that all this talk about sustainability and climate action (even loss and damage) is empty talk. When pockets are filled, mouths shut,” Santos said.

Would swinging public opinion to their side have helped pressure the DPWH and Samal City to realign the bridge?

“When politics (and the China connection) and the exchange of money are involved, nothing short of physical obstruction will work,” she said. ”But I do not think it is about us swaying public opinion, it is about government (from national government) to local LGUs executing their governance and commitment, faithfully and with integrity.”

(Next: Disinformation mars environmental protection of Samal Island)

(This story was made possible by a grant from Internews’ Earth Journalism network through the Asian Center for Journalism at the Ateneo de Manila.)