IN THE mist-laden valley of Marilog village lives the Matigsalug, or “people of the river,” one of the indigenous tribes that inhabit the hinterlands of Davao City, Philippines.

The Matigsalug sustain themselves through traditional farming, cultivating rice, root crops, and vegetables. They rely on the natural rhythms of the dry and wet seasons to guide their planting cycles.

Norma Ramirez, 58, a farmer who leads local women in seed banking—a practice of preserving rice seeds for the next planting season—said it has become increasingly difficult to maintain this tradition in recent years.

“In the past year, it has been a challenge to survive solely on our farm produce. The rains no longer come as expected, and when they do, they bring floods and landslides. We don’t irrigate our rice fields because we plant upland rice, which relies on the quality of the soil. But that’s no longer working for us,” she said.

Marilog is one of the 180 villages in Davao City. Sitting at 2,536 feet above sea level and near the rainforest, the area allows farmers to grow root crops and vegetables for their own consumption.

Davao City, a vital agricultural hub in Mindanao, Southern Philippines, faces a hidden threat on its fertile lands and threatens its bountiful harvests. Often unseen and underestimated, soil degradation is weakening the foundation of agriculture here, leading to decreased crop yields and contributing to food insecurity.

The impact of soil degradation on Davao City’s agriculture translates to reduced income for farmers and decreased food supply for the city’s increasing population. This decline in agricultural productivity could have a serious ripple effect on the local economy, affecting related industries and livelihoods.

In Davao, soil degradation also contributes to environmental problems such as sedimentation of waterways, loss of biodiversity, and increased greenhouse gas emissions. All of this ties back to agriculture:

Degraded soil raises agricultural costs in the region, which can lower farmers’ household incomes, and ultimately may be causing them to abandon their farms altogether.

Soil as diminishing resource

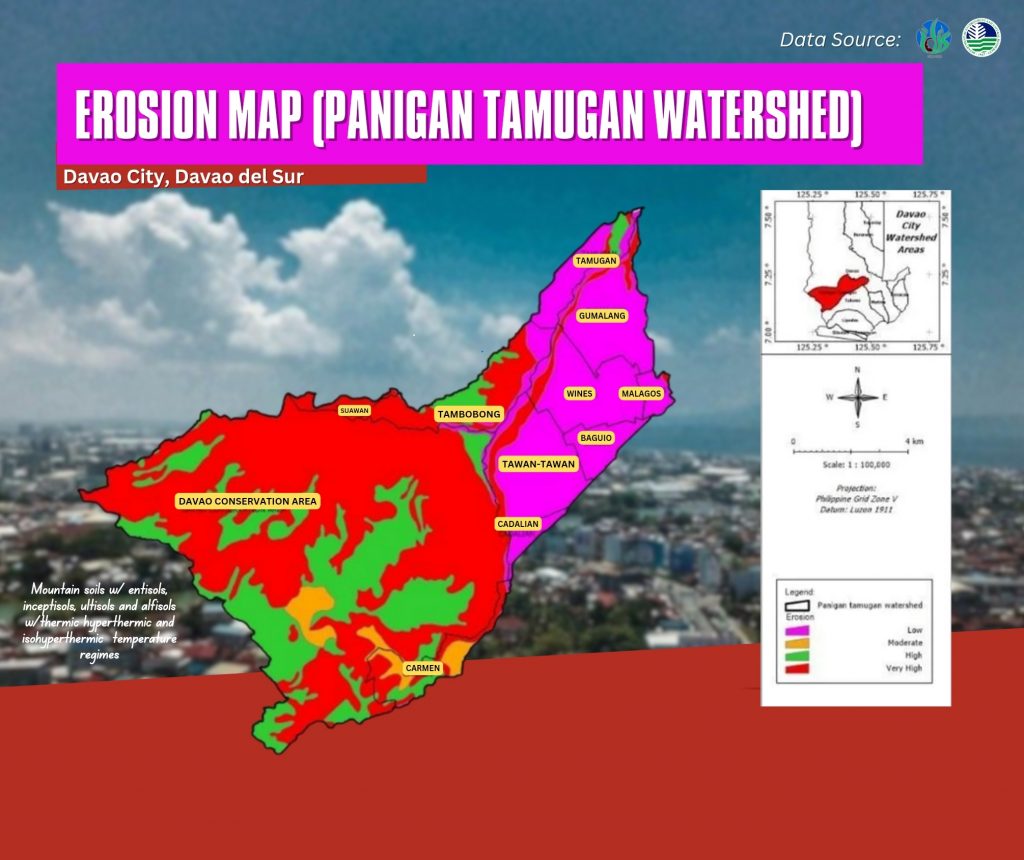

Soil degradation in the city is having significant negative impacts on upland and watershed areas. The shift from diversified farming to monocropping, driven largely by the expansion of banana plantations and economic pressures, has reduced soil fertility and contributed to erosion. Practices such as slash-and-burn cultivation and the use of steep slopes for farming further degrade the soil, leading to decreased organic matter, nutrient loss, and a reduction in the soil’s capacity to retain water.

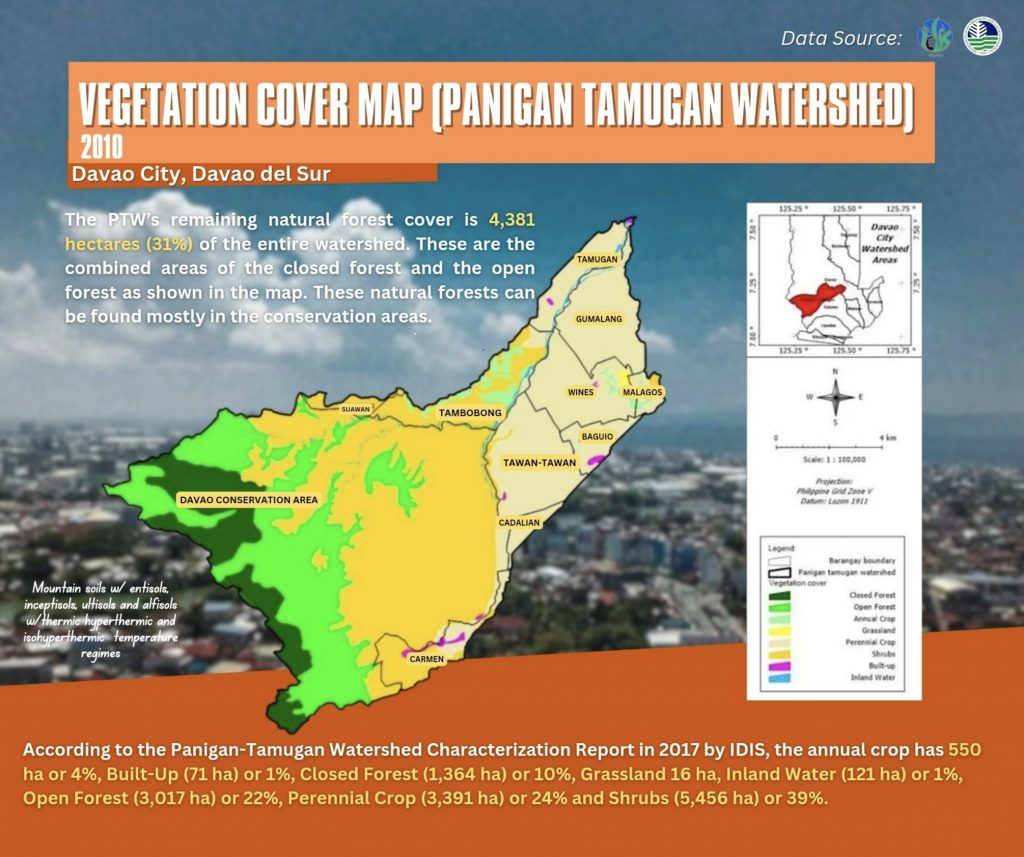

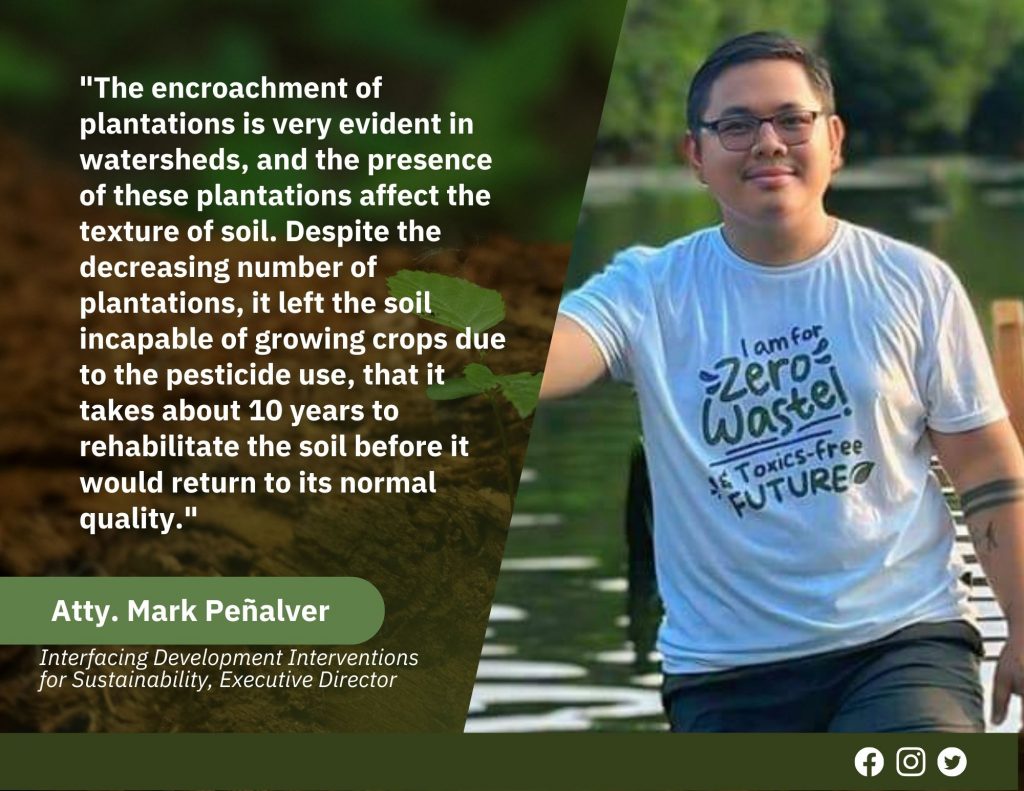

Mark Penalver, executive director of the environmental group Interfacing Development Interventions for Sustainability (IDIS), said that to understand the soil situation in Davao City, one must look at the Tamugan-Lipadas watershed, particularly the Panigan-Tamugan sub-watershed.

This watershed is critical for Davao City as it has been identified as the primary source of the city’s future drinking water and a biodiversity hotspot, home to a rich variety of plant and animal life, including many endemic and threatened species. Protecting the watershed helps preserve this biodiversity.

“Improper and continuous cultivation of hilly lands specifically in Barangays Carmen, Tambobong, and Tawan-Tawan cause soil erosion and a decrease in water holding capacity of the soil resulting in low farm productivity: leading to lower income and eventually poverty,” he added.

Increased agricultural activity in sensitive areas, like riverbanks and steep slopes, exacerbates soil erosion, which not only diminishes the productivity of farmland but also contributes to watershed degradation. This, in turn, leads to increased flooding and sedimentation in lowland areas, further disrupting agricultural activities and the livelihoods of farmers.

Citing the 2017 report of IDIS and the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR), Penalver said that the cultivated area covers a total of 550 hectares of the entire watershed and that low-lying areas, particularly areas of Tamugan, Gumalang, Wines, Tambobong, and Tawan-Tawan experience flooding during heavy rainfall.

As soil health continues to decline, crop yields are likely to decrease, and the reliance on chemical inputs may increase, leading to a cycle of soil depletion and environmental harm. To ensure sustainable agricultural productivity, interventions such as soil conservation, organic matter enrichment, proper land-use planning, and the protection of watershed areas are essential for Davao City’s long-term agricultural viability.

Monocropping and Plantations

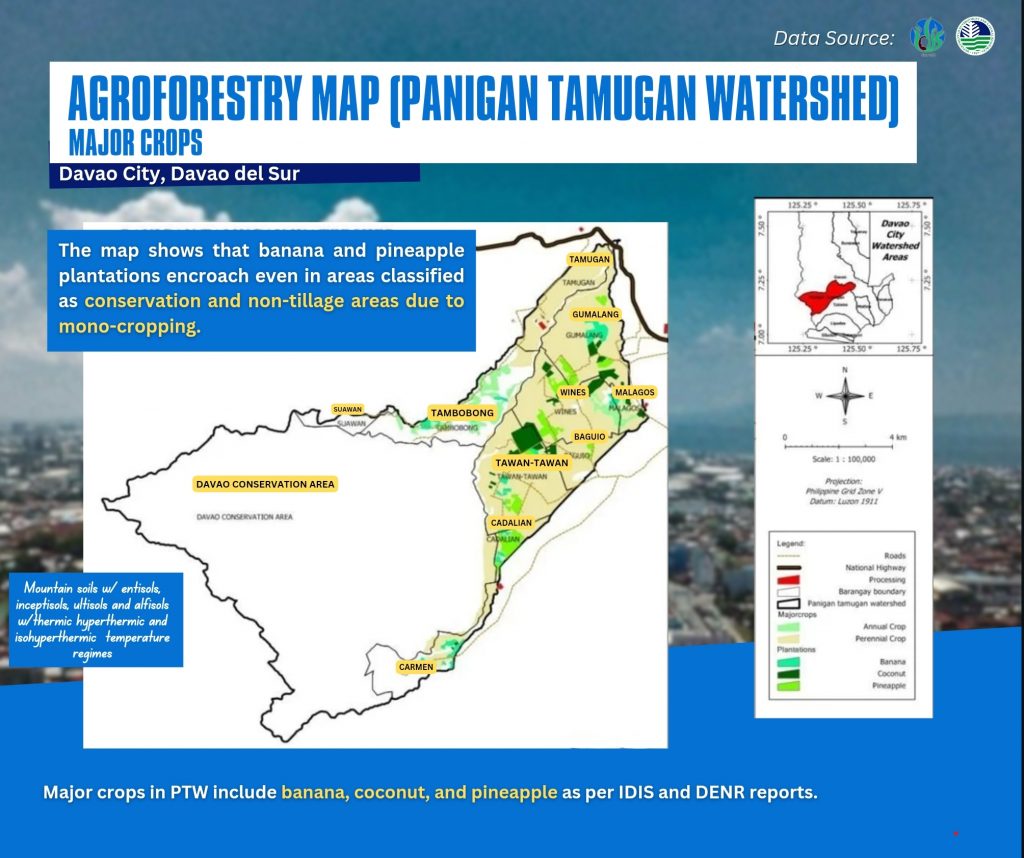

Monocropping, the agricultural practice where a single crop species is grown repeatedly on the same land year after year, often leads to soil depletion and increased vulnerability to pests and diseases. And it’s a problem in Davao:

There are 14 agricultural establishments and plantations in the city that were issued Industrial Environment Compliance Permits by the Environment Management Bureau.

The Talomo-Lipadas and Panigan-Tamugan Watersheds Resource and Socio-Economic Assessments by Jayson Ibanez of Philippine Eagle Foundation in 2012 cited that the agency granted a total of 4,809.95 hectares of banana plantation in five districts of the city in 2005.

Based on the field visits conducted by the researchers to four randomly selected barangays, they observed a shift in agricultural production from diversified farming to monocropping.

When TIMES visited these barangays this year, it was clear that areas planted with bananas by sub-contract growers have expanded.

The 2012 report showed that in Tambobong, the hills have been planted with bananas by SUMIFRU, a banana company that has farmed a total of 134 hectares in the area since 2005. These plantations cover about 16% of the barangay’s total land area (862 ha).

In Barangay Carmen, four out of nine “puroks” (neighborhoods) have been planted with bananas by DOLE and private growers. About 35% of the barangay’s total land area has been converted into banana plantations in recent years, according to barangay officials.

In Barangay Manuel Guianga, SUMIFRU operates around 500 hectares of banana plantations, while Ayala/HBC manages 90 hectares, and DAVCO runs 30 hectares. The area for banana cultivation is estimated to be around 150 to 200 hectares. This data indicates that over 50% of the barangay’s total land area of 1,400 hectares is dedicated to banana plantations.

At Daliaon Plantation, the banana plantation area is estimated at 400 hectares, with about 200 hectares (or 50%) located in sloping A-NT areas, according to the barangay captain. Most of the banana plantations in the barangay are operated by private growers.

The report further explained that the hectarage of banana plantations continued to increase, as smallholder farmers were enticed to shift to monocropping, driven primarily by economic factors.

“Barangays Tambobong, Carmen, Tamayong, and Daliaon Plantation have been classified as A-NT areas by the MGB terrain study but large-scale, commercial plantations continue to operate in these areas. Agricultural encroachments into the conservation zone were also reported at Sirib, Tamayong, Daliaon Plantation, and Manuel Guianga,” the report reads.

Plantation farming is the city’s dominant land use. This type of farming becomes dependent on pesticides as every cycle in its production process involves regular application of the chemicals.

The proliferation of plantations then pushes small farmers to also be dependent on synthetic pesticides in their farming practices. They cannot get out of the cycle as all pests targeted during the regular application of pesticides from the big plantations will transfer to their farms nearby.

Stephen Antig, executive director of the Pilipino Banana Growers and Exporters Association, Inc. (PBGEA), recognizes the need for interventions hence they employ annual soil analysis, calling it “annual recommends.”

Formed in 1969, PBGEA aims to look after the collective needs and concerns of the players of the local banana industry so that it may remain competitive and keep its position as among the top exporters in the world.

Antig said it is important to introduce interventions to keep the soil healthy but most of the growers cannot afford additional investments.

Banana, unlike many other crops, is only planted once, as it is a perennial crop. For every banana planted, there are two suckers or followers from which the healthier one can be chosen to grow.

There is no need to re-plant and re-develop after each harvest which disturbs the condition of the soil. One way to control fusarium wilt, a disease of bananas, is really by improving soil nutrients and condition, as fusarium wilt is soil-borne, and will remain in the soil for 30 years.

Slash and burn

There are other threats to soil health in Davao, some of which are more complicated to tackle. A 2017 IDIS report highlighted that upland cultivation is the primary source of livelihood for upland dwellers, most of whom are indigenous peoples.

“Slash-and-burn” or swidden cultivation is common, especially in areas dedicated to cash crops such as corn, sweet potatoes, cassava, and other short-term crops. Some indigenous peoples to this day continue to practice this form of shifting cultivation. In areas farmed by non-indigenous groups, crops like durian, coconut, rambutan, lanzones, and other high-value species are planted alongside annual cash crops.

Leo XL Fuentes Jr., regional coordinator of Magsasaka at Siyentipiko para sa Pag-unlad ng Pilipinas (Masipag) Mindanao, a farmer-led network of people’s organizations, said the notion that “slash and burn farming” is unsustainable is “not entirely true.” In small areas, it is actually beneficial for both the people and soil microbiome as this type of farming includes the fallow or rest period for the soil.

“In the context of Davao City, there are specific risk factors to consider if people are practicing slash-and-burn agriculture. For example, the dominant vegetation, which is usually cogon (wild grass), is very risky as it might cause forest fires. But we need to note that the dominance of cogon is just a result of the massive logging activities done in the past,” he added.

However, the growing upland population is placing increasing pressure on forest resources. Many critically sensitive areas, such as steep slopes and riverbanks, are being used for agriculture and settlement. This contributes to watershed degradation, resulting in soil erosion and flooding in the lowland areas during the rainy season.

The agricultural areas which are mostly found in lowland barangays include perennial crops, with an aggregate area of 3,391 hectares or 24% of the entire watershed. Crops planted include rice, corn, coconut, and fruit trees such as lanzones, rambutan, and durian, among others.

Joshua Donato, Field Biologist of Euro Generics International Philippines (EGIP) Foundation, a Davao City-based environmental advocate, though, said swidden cultivation usually leads to deforestation. He argues that farmers will eventually move to another area when the fertility of the soil on their farm is exhausted due to continuous burning.

“Burning can deplete nutrients in the soil over time. It can also reduce soil permeability, infiltration rates, and water holding capacity – making the land more prone to flooding, erosion, and desiccation, especially in a watershed areas that regularly and frequently experience rainfall,” he added.

The biologist added most indigenous communities still practice swidden farming due to economic conditions and inaccessibility to new technologies and applications that the government introduced. “Worst, they don’t have enough resources to compete with those big companies and capitalists that utilize big areas to do farming or plantations,” he added.

Agriculture in the uplands

Yet the lowlands aren’t the only area where soil degradation presents a problem. Even as local forest guards called “Bantay Bukid” exert effort in protecting the uplands, the problem of continuing soil degradation is observable, due to the absence of effective on-site management.

Bantay Bukid volunteers serve as the front liners in protecting the upland water sources by enforcing environmental laws, doing reforestation, conducting biodiversity and river monitoring, and serving as first responders in disaster preparedness and response in Tawan-tawan, Baguio District, Davao City.

According to experts, among the activities observed are the improper and continuous cultivation of hilly land specifically in the upland villages of Carmen, Tambobong, and Tawan-Tawan; timber poaching; a settlement in steep slopes and the slash and burn practice; illegal occupancy within forestlands; encroachment of monocrop corporate plantations in conservation and non-tillage areas such as banana and pineapple; soil erosion; and deforestation and land use change.

Nena Morales, 72, a local scientist who runs a two-hectare demonstration farm called “Imulayan Resource Center” for organic farming in Tugbok district, said the issue of soil quality in upland communities is the elephant in the room.

“When we talk about agriculture, the focus is always on problems like farm-to-market roads, agricultural inputs, lack of post-harvest facilities, limited capital, and farmer training. But we often overlook the issue of soil quality, which is right beneath our feet,” Morales said.

She is working with women farmers in research and development to improve crop yields and make organic farming viable.

However, there are new threats to contend with: Due to reduced productivity, farmers in the uplands prefer to sell their lots to real estate developers.

Penalver said the selling of undeveloped lots is common especially in the Tawan-Tawan District due to the poor soil quality, which is not compatible with growing crops.

“If they plant, there is a possibility it will not last or even grow due to the toxic quality of the soil, so they would rather sell the lots rather than invest in planting crops that might not survive,” he said.

Shift to sustainable practice needed

The decline in soil health poses a significant threat to the city’s and surrounding watershed’s food security and economic stability. Driven by factors like monocropping, unsustainable farming practices on vulnerable lands, and deforestation, soil degradation leads to reduced crop yields, lower farmer incomes, and environmental problems like erosion and sedimentation.

For Patrick Jerome Guasa, Environmental planner and System of Rice Intensification advocate, said soil is a crucial element in agriculture. Healthy and productive agriculture is largely dependent on soil health while the health of the soil is dependent on how the farmers manage it and vice versa.

“Degraded soil raises agricultural costs, which lowers farmers’ incomes, causing farmers to abandon their farms. Keeping the soil rich and healthy will raise plant management costs,” he said.

This jeopardizes Davao City’s long-term agricultural viability and the livelihoods of those who depend on it.

The special report, based on the Crops Production Survey (CrPS) by the Philippine Statistics Authority, which was released in August 2024, the volume of production of fruit crops in 2023 declined to 0.5 percent compared to 2022.

In 2023, as seen in Figure 1, the Davao Region produced 3,457,906.64 metric tons of fruit crops, which declined by 0.5 percent from 3,474,562.63 MT in 2022. The decrease was mainly attributed to the production drop of bananas by 17,573.23 MT between 2022 and 2023. Fruit crop production likewise dropped by 1.16 percent from 2021 to 2023.

A shift towards sustainable practices is needed at this critical time. Implementing soil conservation techniques, enriching organic matter, promoting proper land-use planning, and protecting watersheds are crucial steps toward ensuring a healthy and productive agricultural future for Davao City.

For people in the uplands, there is a direct connection between soil health and survival. Matigsalug farmer Norma Ramirez, who continues to promote seed banking as a way to ensure the availability of heritage rice for generations to come, said “We depend on the land for sustenance and a soil that is not healthy is a threat to our existence.” Report by Amalia Cabusao, Nova Francas and Maimona Wanda Lao