(Second of two parts)

ENVIRONMENTALISTS and resort owners in Samal Island said misinformation and disinformation “coming from the highest levels of government down the line” have blocked efforts to protect the island’s natural environment, as the government goes full steam on its Samar Island-Davao City Connector (SIDC) bridge project.

Environmental planner Carmela Marie Santos, director of the environmental arm of the Ateneo de Davao University Ecoteneo, said, “You hear the Department of Public Works and Highways say that corals are dead,” justifying construction in the area.

A study commissioned by the Rodriguez Family that owns Paradise Island Garden Resort, a resort that will be affected by the SIDC construction, revealed that the reef at the center of the controversy stretches 300 meters long and 50 meters wide. Known as Paradise Reef, it is home to about 100 species of fish and another 100 species of soft and hard corals.

The study was conducted by scientists Dr. Filipina Sotto, Dr. Cleto Nañola, and Joey Gatus and debunked the claim that the reef was dying. The scientists instead warned that continuing the current path of the bridge would “cause irreparable, irreversible and incalculable damage to the best marine ecosystem in Samal Island.”

Marine biologist John Michael Lacson, who volunteered to help the family, said Paradise Reef is considered a spawning site and the coral polyps would not survive the siltation and sedimentation caused by the dredging and construction.

Santos accused the Department of Environment and Natural Resources of disinformation after its personnel conducted a dive in November 2023 supposedly to take photos showing Paradise Reef as dying. The photos were posted on DENR’s Facebook page. Santos however said the diving team was “hundreds of meters away from Paradise Reef.”

Samal Island, formally known as the Island Garden City of Samal (IGaCoS), is a third-class municipality and amalgamated city consisting of three towns—Babak, Kaputian, and Samal. With 30,100 hectares of total land area, IGaCos only has 116,771 residents based on the 2020 Census. Separated from Davao City by the Davao Gulf, it has become the go-to destination for families seeking respite from the urban jungle and tourists wishing to enjoy its white-sand beaches and the time that crawls to a halt.

IGaCoS is also a biological hotspot, its name “Garden City” owing to its diverse flora and fauna, including one of the most biodiverse marine ecosystems in the country.

For instance, of the total 73 genera of identified corals in the country, 53 are found in Samal. The same goes for the nine in 13 species of seagrasses. It’s also a favorite of dive enthusiasts and underwater photographers because Samal Island is also home to 250 species of aquarium fishes and nine of the 27 species of cetaceans in the country.

The island plays host to 15 species of bats. In fact, IGaCoS is home to the Monfort Bat Sanctuary, which holds the distinction of being listed in the Guinness Book of World Records for being the colony of 2.3 million Rousette bats.

Disinformation slammed

On June 10, the Sustainable Davao Movement (SDM), an alliance of Davao City-based environmental groups, released a statement slamming the misinformation and disinformation promoted by the DPWH. The group said the agency “has been consistent with misleading and false information that they give on media with regard to the environmental impacts of the SIDC Project/Samal bridge.”

Citing the studies, SDM said the coral condition is as good to excellent based on live coral cover and biodiversity. The SDM belied the claims of the DPHW–Unified Project Management Office-Bridges Management Cluster (UPMO-BMC) that the project did not result in coral destruction, that it would use curtains to curtail damage, and any damage could be easily replaced.

SDM released photos taken in February 2024, which reportedly showed how siltation, sedimentation, and turbidity caused damage to the corals.

As to replacing the corals, the SDM said the cost could balloon to P223 million at the estimated P22,281 per square meter of restoration cost. However, it excludes the fish productivity loss considering the site has nearly 50 metric tons per square kilometer of biomass.

Meanwhile, the group also slammed lawmakers for “feigning ignorance” when the contractor cut over 200 trees to prepare the landing site in Lanang, Davao City. SDM claimed to have sent a letter to the Office of the City Mayor dated March 27 warning about the plan to clear the area of mature mahogany trees.

The group cited the Heritage Ordinance (No. 1784), passed by Davao City in 2021, which seeks to preserve and protect mature trees that provide cooling and shade.

Much to their surprise, a billboard showing the DENR permit to cut the trees was erected on-site amid all the felled trees on the ground, which Atty Peñalver lamented was Exhibit A of what the government sacrificed in the name of progress.

No More Realignment

However, at this point, the environmentalists and the resort owners might have been preaching to an empty pulpit.

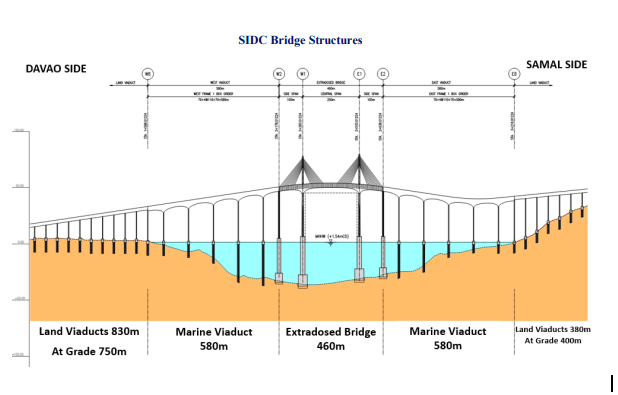

For instance, the detailed engineering design covering the bridge’s alignment is already finished and they are on pace to complete the project by September 2028.

Engr. Rodrigo Delos Reyes, project director based in DPWH Central Office, said, “Sa ngayon po palagay ko, kita niyo naman kung anong takbo ng trabaho, kung mag realign tayo baka malaki ang pera masasayang natin sa ating accomplishment (For now, I think, you can even see the scope of the work, if we realign now we would have wasted a lot of money),” he said in a press conference here in June 2024.

The contractor has also already installed more than half of the total 74 bored piles for the bridge and it would not be feasible to pull them out again. Bored piles are cylindrical concrete bodies buried on the marine floor to support structures with heavy vertical loads.

Bored piles are used as alternatives to the traditional concrete pile to lay down the bridge’s foundations. “We use bored piles to drill a hole into the ocean floor. After drilling, we bring down a steel cage before pouring the concrete, so it’s self-contained,” said the DPWH XI spokesperson, adding that the technology would minimize damage to the ocean floor.

In contrast, the original design was potentially very destructive since each pier and foundation could take the space of a basketball court.

The original timetable for the turnover was in 2015 after six years of construction. However, the global pandemic and right-of-way problems—10 lots on the Samal side and four on the Davao City side—pushed the project back.

Delos Reyes also said they cut 294 trees in Davao City and 192 in Samal City but these were all covered by the required permits. As part of their commitment, they also planted nearly 30,000 trees in Davao City and 1,200 in Samal Island to replace the felled trees.

Meanwhile, Engr. Joweto Tulaylay, SIDC project manager, said there is stopping or realigning the project, short of a temporary restraining order from the court. He also said they needed the Chinese’s expertise in building the bridge, which explains the presence of foreigners on the project site. However, the contract called for a 70:30 ratio of labor pool in favor of local hires.

The Power of Public Opinion

Peter Laviña, the former campaign coordinator of President Rodrigo Duterte and National Irrigation Authority administrator, said the original plan was to connect the bridge to Panabo City in Davao del Norte on the mainland and the tip of Samal, which had fewer resorts.

He said public opinion holds sway in government infrastructure projects. However, he could not say for certain if the advocates could swing the people to their side.

Nonetheless, he cited some successful campaigns where public opinion was a factor in changing the mind of the national government. For instance, the Sasa Port Modernization project in 2015 was scuttled when groups raised the alarm over how politicians jacked up the cost from the original P5 billion to P15 billion to fund their election campaign.

“We united the public, port operators, the (Davao City) chamber (of commerce), plus the city council to expose the plan and oppose it. We reached the Senate for public hearings and filed a suit before the SC.

“We galvanized the public opinion against it and DoTR Secretary (Joseph Emilio) Abaya and PPA eventually shelved the plan,” he added.

For his part, Lucas lamented that public perception was hardly sympathetic to their plight because they thought the family was rich and the government would pay them anyway. But he quickly added that it’s not about the money. He said the family doesn’t depend on the resort’s income to live comfortably since they have other businesses and properties.

“We are not politicians. They (government and contractor) are brazen because they know that public perception is on their side,” he said.

The resort owner told this author that he and his three siblings are taking consolation in the fact that their mother passed away in 2018.

Their mother always reminded them that they were gifted with a precious blessing—the privilege of being stewards of the environment.

“But what they did to the place… it would have broken her heart,” he said.

“Would it have changed the government’s minds to realign the bridge if we worked with environmental groups earlier to convince people?”

“Perhaps or perhaps not,” Lucas said.

“But we are not the losers, the true losers are the century-old corals, which were classified as spawning grounds for the Celebes sea. And they might not realize it yet, but the true losers are the people,” Lucas added.

(This story was made possible by a grant from Internews’ Earth Journalism network through the Asian Center for Journalism at the Ateneo de Manila.)