“It is not only once that I dreamed of Davao and the dear Doctor and his family since I was repatriated to Japan. The peaceful and undisturbed life I used to enjoy at the Dakudao Plantation, the happy gatherings in the Dakudao residence in Tugbok, the plentiful and big bananas and mangoes that were so sweet and delicious, my humble self who was engaged in surveying the fertile and extensive virgin land of Malagos many years ago…These were some of the subjects I dreamed of so often. And every time I dream, I dream of Davao and the dear Doctor…The subjects of happy conversation at our home are almost invariably the topics on Davao and the dear Doctor.

The happiest and the most peaceful years of my life were those when I worked in your plantation. I shall never be able to forget the dear memories of the plantation for I lived there and worked there for almost twenty years…”

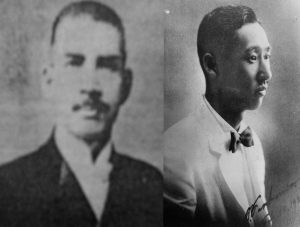

This was lifted from a letter dated December 20, 1948, written by a Japanese national named Migitaka Kenichi to my late grandfather, Dr. Santiago Pamplona Dakudao, Sr. From Migitaka san’s letter, it can easily be discerned that for the Japanese pioneers of Davao, there was no greater sorrow than to recall, in misery, the time when they were secure, happy and leading productive lives in prewar Davao. Davao, during that period, was well-renowned as the country’s “Land of Promise” for the many opportunities it had to offer. It is no wonder then that a majority of these Japanese, particularly the Nissei or the second generation Japanese who were born in Davao, consider Davao their “furusato,” their second homeland.

Perhaps, only a few Davaoenos of the generation born after WWII know of the Japanese role in the pages of their City’s history. A few years back, so many would wonder why sometime in August of each year, a considerable number of aging Japanese would come in droves to visit Davao City in celebration of their Obon which is similar to our All Souls Day. These “Davao Japanese,” as Filipinos would refer to them in the past, would also take the time to visit, always bearing omiyage or what we know as pasalubong, the families of their former Filipino landlords; and renew contacts with friends and acquaintances from way back. Still others would donate balikbayan boxes full of used clothing to mestizos of Japanese-Bagobo parentage found scattered all over Davao. It was, indeed, an emotional event for the Nikkeijin (second generation Japanese) who were born in Davao, who referred to their annual pilgrimage to Davao as their “sentimental journey.”

“Even if your child who is born in this southern country visits Japan, he would always like to go back to the South,” just as it was prophesied in an article which appeared in the Mainichi Shinbun dated August, 1916, aimed to attract the youth of Japan to go and settle in the Philippines which was then under the American rule.

In the early part of the 20th century, Japanese nationals were going abroad in centers of economic activities like in Hawaii, California, and Brazil in search of a better life in much the same manner as citizens of the underdeveloped countries are presently doing. The Japanese Government then was actively exporting its human resources owing to the fact that it deemed its population too big and the rate of its growth too fast for its limited land and other natural resources. This motive would get additional promotion with developments in the US-Japan relations, and Japan’s goal of pan-Asianism in the 1920’s and 1930’s which saw a big change in Japanese policy towards emigration to Southeast Asia. Before WWII, the largest group of overseas Japanese workers in Southeast Asia was concentrated in the area around Davao. Of the entire Japanese population in the Philippines totaling to about 19,000 between the years 1904 to 1935, 80% were concentrated in Davao. By 1939, the Japanese that lived in Davao numbered 17, 888. Davao then was in desperate need of laborers to open up its vast virgin lands; and Japan was able to expand its import-export trade to the Philippines, an area rich in the resources that Japan lacked and needed to support its growing industries at that time.

While in the Philippines, the Japanese engaged in many different trades and industries but they had specialized, concentrated and made their mark in one of the basic industries: the growing and marketing of abaca or Manila hemp. Davao was considered then the most ideal agricultural territory for growing high grade abaca owing to its fertile soil and suitable weather conditions. Most of the abaca was produced and exported from Davao than from any other point elsewhere in the Philippines. As such, it was closely tied to the world economy and international affairs as abaca dominated the cordage market during that period. The Philippines then had a virtual monopoly on abaca, which was considered at that time as the “longest and strongest cordage fiber in the world that its tensile strength is about double that of the Mexican sisal, its chief competitor in the USA.”

It was remarkable that the Japanese developments were achieved in a brief period of time spanning less than 40 years.

The scope of the Japanese settlement in Davao and the progress which it was achieved were attributed to the persevering industry of the Japanese settlers as well as to the foresight and entrepreneurial leadership of a small group of shrewd and determined Japanese adventurer-businessmen like Ohta Kyosaburo and Furukawa Yoshizo. Ohta and Furukawa each Davao and represented a tangible link with the Mother Country, Japan. The survival of the Japanese agricultural colony in Davao was undoubtedly secured by a common sense of purpose, related to larger Japanese national ends, and by the presence of these leading authoritarian company administrations.

It’s been a century since the Japanese laborers landed on Davao soil and toiled their way in a pioneer agricultural settlement armed with the hope of acquiring a better future for themselves and their generations to come. How the wheel of fortune has turned, indeed. Sadly, it is now our country who has been into the business of exporting OFWs to Japan and to the other parts of the world.