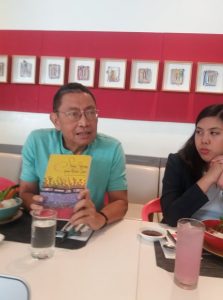

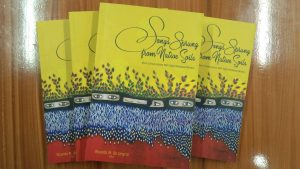

Where Philippine literature is concerned, award-winning writer Ricardo M. de Ungria has had enough of the idea of a periphery. De Ungria’s new book, Songs Sprung from Native Soils, launches next year in Cagayan de Oro where the Xavier University published his interview of eight Mindanao writers.

Where Philippine literature is concerned, award-winning writer Ricardo M. de Ungria has had enough of the idea of a periphery. De Ungria’s new book, Songs Sprung from Native Soils, launches next year in Cagayan de Oro where the Xavier University published his interview of eight Mindanao writers.

As far as De Ungria is concerned, “periphery,” or a “margin,” is not only patronizing as it is insulting for writers coming from the regions. In fact, he calls for the death of the concept. Off with their heads.

De Ungria analyzes and criticizes the artistic structure in the country and says there should be a more empowered vision for writers in areas like Mindanao, away from an idea of a creative “center.” Namely Manila.

Now those who know the guy could find this odd; after all, he was a professor in schools like the University of the Philippines-Mindanao and has been a Commissioner for literary arts in the National Commission on Culture and the Arts (NCCA).

But this is where his seething anger lies, throughout years of observing how works by literary writers from different places are almost always identified vis-a-vis a standard Manila, or worse, a uniform American concept.

The point of view is to encourage the writers to forget Manila and the center/margin dialectic discourse, he tells the TIMES. “Dapat isipin nila na sentro sila ng sariling interes (the writers should think of themselves as a center of their own interest),” he says.

The book features his interviews with eight Mindanao writers, namely Leoncio Deriada, Noralyn Mustafa, Jaime An Lim, Christine Godinez Ortega, Calbi Asain, Lia Lopez-Chua, Telesforo Sungkit, Jr., and Almayrah Tiburon.

The interviewees featured are a combination of writers who are Muslims, Lumad, transient, resident, Mindanawon all, whether they be born here or whether they decided to call the place their own.

“It is the landscape that defines vision,” De Ungria says in the TIMES interview. “Importante ang discourse ng landscape kung nasaan ka dahil iyon ang nagbibigay sa artist ng inspiration kung anong gagawin niya.”

This, he says, is the reason different writers see different things depending on which region they area. He claims Manila demands an artistic homogeneity. De Ungria introduces the book by saying “Philippine Lit” should include more of the silence encouraged by featuring more English and Tagalog work as representative of the entire collection of art here.

“Maraming kulang diyan,” he says. “Hindi pa nabubuo ang Philippine literature, mayroon na agad tayong Philippine literature.” But this one is in our own language, a language owned by those writing in their own cultural milieu.

But what of his own role in the propagation of this monster called literary colonialism? What of the Postmodern? “Since I retired, I have refused invitations to teach and sit at panels of writers workshops because this perpetuates the coloniality of our being,” he says. “The writers should use this tool, kasi maiintindihan ka eh,” De Ungria says.

“I’m burning my bridges, with everything that’s behind me. I cannot undo that. I was a creature of my age. I don’t want that to happen to the young ones now. the older you get, you’ll realize ‘bakit english ang ginagamit natin na framework dito? Wala namang kinalaman sa buhay natin. Ibang klase sila mag isip,” he adds.

“I’m burning my bridges, with everything that’s behind me. I cannot undo that. I was a creature of my age. I don’t want that to happen to the young ones now. the older you get, you’ll realize ‘bakit english ang ginagamit natin na framework dito? Wala namang kinalaman sa buhay natin. Ibang klase sila mag isip,” he adds.

And so over the years since his retirement, De Ungria has been on the prowl for works that defy literary conventions but define an own culture. He remembers a work he read at one of the writers workshops here, something a teacher from a public school wrote about. What drew him to the story is the level of detail: it was about a Lumad initiation rite that he had not heard about before.

He was himself surprised he was defending the work, as some early drafts are at workshops. The grammar was not there yet, the structure too. But where De Ungria dwells now in his search for the next great Philippine literature is something old yet new. He is a shark smelling blood across larger Philippine seas.