It’s almost a stone’s throw from our own office at Palma Gil. In this portion of the city, there is a corner in Bonifacio and Ponciano where the noise blaring from Toril’s infamous uso-uso jeeps ends and the adrenaline and beer-fueled rock music begins.

This hole in the wall sits across what used to be the old Queens theater along Bonifacio Street. But if you listen closely, the songs from the bands are barely familiar for one of two reasons: the genre is foreign to you, or, more often than not, it is the song itself that’s new: what rock music is supposed to sound like.

Welcome to one of the few pocket havens of original rock music in the city. Gioscrib (jee-yos-crib) has been around for at least three years at the old location of Barbecue Bob’s.

At first glance last Sunday, it appears as rock and roll as it sounds: there is beer (of course), loud music, at the tables nearest the stage are tattoo artists needling ink into skin while the amplifiers blare a more welcome noise. Even as I take notes for this article one of the passing bandmates hits my knee with a bass guitar coffin. The band dude apologizes, and I nod. Hardcore. Somewhere in the crowd a caucasian DJ covering independent music in Asia is himself drunk, covering the gig as a music journalist based here for weeks at a time. He gets one of the 3×3 tattoos himself. Rock and roll.

But this gig isn’t ordinary, this one is for a cause. “Tinta Para kay Ina” was organized as a benefit gig/tattoo festival for one of the bar’s friends and patrons: Olong Albarillo, whose mother Nilda, 61, is in the hospital for surgery and therapy for several cases, among these her ovarian cyst, which was followed by a bout of stroke and bleeding complicated by diabetes. The family takes turns watching over Nilda, while Olong’s father Nido usually stays around to help with the mother’s needs.

“We’re usually closed on Sundays,” Giovanni Gaite, the bar’s namesake, tells the TIMES over a few bottles last Saturday.

“We’re doing this for our friends and we don’t mind sharing the space.”

But Gaite is being more than modest. Other than the patron orders, none of the proceeds goes to the bar. The entrance fee for the Sunday nighttime gig was only P30, and the bands were more than willing to play music for a cause. Playing last Sunday were The Hospital Doors, Spooky Serna, Moawh, Jonah, Acid Radius, and Tagum-based The Gymboys. The vocalists remind the patrons to pass the hat, glass, or, well, bucket, but this time for a cause.

The project started as an idea by Olong’s partner Lexi Acosta, herself a tattoo enthusiast. Eventually, Gio’s wife Taj pitched in and offered Davao City as an alternative location.

Even with an HMO enrolment, the family’s income isn’t enough to pay for all the medical bills that Nilda’s case has accumulated for the past month. And so, Olong turned to his other family: the scene itself.

“The idea actually started in Marbel, where we originally intended to hold the ink for a cause,” Olong said. But as word spread online about his mom, it became logical to hold the event here, with samaritans like Gaite more than willing to share the roof of his small corner of the city.

The gig is as rock and roll as it gets. During the short walk starting from the entrance towards the main bar area, the walls are lined with album covers of bands such as Metallica, Pantera, and Slayer. At this night’s gig, there was live rock music of various genres playing as needles and ink met skin. Booze and drunken conversations competed with the noise, at least six local bands rocked the small stage with music as fun and fearsome as gigs go.

“In a way, we’re trying to help the scene,” Gaite said. “There are barely any places in Davao where the bands can play the gigs.” And in places where they can, the support is a handful. One could tell that the people at the bar were regulars, or at least were Olong’s friends. The Davao band scene is, as it stands, still dominated by cover bands and local artists remain a minority.

“It’s not a lucrative source of income. At least not yet. Not anymore,” Gaite says of the money being made. “What we have now is mostly fueled by individual and group passion.” This is bewildering, in the age of internet and even amid the emergence of genres such as Bisrock (Bisaya rock coming from the Visayas) and the Cebuano language music in general. (I think this part is where my editor’s going to chime in her favorites: the music she listens to inside her Wigo during her drives home).

There’s Spotify, and across other genres local independent acts like Anne Mendoza, RJ Manulid, and Spill Harbour are inching their way towards viral streams online. There are bands like THEA that are getting it right.

While rock and tattoos have been historically associated with rebellion and almost mandatory rule-breaking, Gioscrib breaks that mold with Gio himself, the burly, bearded heavily tattooed dude you would never think of crossing. But Gaite is actually a church group leader every weekend. He has three kids, and already has a teenager.

“I mean look,” Gio tells us, in between reminding his daughter not to run around the bar while holding a bananacue stick, (Hey, I just told you–). Look, I want to show the world that we’re not shitty people. At least not all of us.” He even mentions a band mostly composed of lawyers.

Albarillo, for his part, dabbles in a private referral-based tattoo business based in Marbel, and in the middle of the interview describes an intricate permitting process for tattoo businesses, as well as the sanitation requirements. “We never reuse needles, that’s absurd! And dangerous!”

Apparently, legit tattoo enthusiasts are picky, too, of their service providers, and generally refuse posers and ones that reek of malpractice. It’s instinct. “It’s almost like a surgery, wherever we are,” Gaite says. The needles are all new; the artists make sure that their clients see this for themselves. Everything is clean and sanitized. And ink is thrown out after use, even if the entire batch of ink for the piece isn’t consumed. Even the Department of Health is involved in the permitting process.

Gaite knows the city like the guitar callouses on his fingertips, having literally mapped most of it for 12 years as a former employee of the City Government’s City Planning and Development Office.

When business came calling, the idea was to simply start a food or restaurant, but the friendships grew the establishment into what it has become three years later after it launched during one Araw ng Dabaw week in 2016.

We ask Albarillo about the proceeds of the gig for a cause, and he tells us, happily that the fundraising raised around P35,000 for P500 3×3-inch tattoos. Seven artists labored throughout the day, starting 10 a.m. that Sunday until around 11 p.m., hours before the city’s liquor ban. Albarillo inked 16 patrons himself. All in all, there were around 60 clients who lined up the entire day to have themselves inked in support of the effort.

For a relatively small amount raised that night, Albarillo and partner Lexi seemed ecstatic, despite the bills piling up as each day passes.

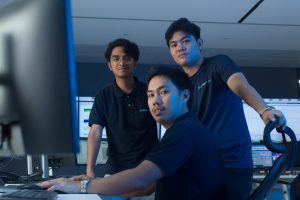

Tools of the trade

Tools of the trade

There’s a slight pinch and prick when we ask where Albarillo works.

Apparently, aside from being a tattoo artist, he is among Davao City’s heroes, working for the famed Central 911’s call center, while he is now scrambling to rescue his own mother to keep her healthy.

If we’ve ever dialed 911, he may have been among those who had saved our lives one time or another.

Without any of us knowing.