A GROUP of dedicated volunteers is turning the tide on marine pollution by collecting PETs, glass bottles, and disposables and upcycling them into eco-blocks and paver bricks not only to protect the Davao Gulf but also provide additional income to poor families living on the waterfront.

The Bantay Dagat Volunteers Association of Davao City has taken an innovative approach to tackling the global issue of marine pollution, transforming weekly collected ocean and river trash into valuable construction material.

The Bantay Dagat Volunteers Association was established in 2017 through Executive Order No. 5 signed by then-mayor and now-Vice President Sara Duterte. It was initially envisioned to clean the shorelines by diligently collecting waste from various parts of the city, replicating the success of the Bantay Bukid in protecting the city’s forests from illegal loggers and poachers.

Mr. Raffy Bermejo, the association president, said they approached families in coastal communities to become volunteers. “At first, they did not know there was an honorarium. So, their motivation was to help clean their surroundings. We make sure not to uproot the volunteers from their community, so they could really see the difference in their hard work.”

The Ancillary Services Unit, under the Office of the City Mayor, monitors and pays the volunteers P1,000 each for three hours of work every Saturday.

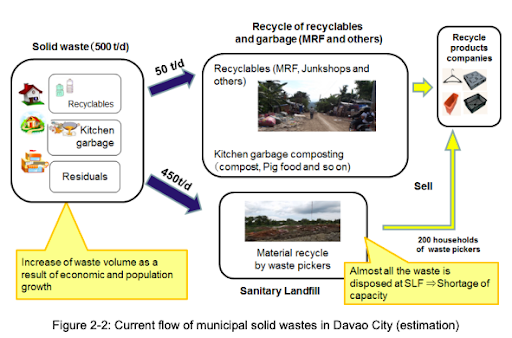

When they were just starting, Mr. Bermejo said most of the marine waste they collected ended up in the sanitary landfill after being turned over to the City Environment and Natural Resources (CENRO). However, he saw the same cycle of inefficiency repeated when the system itself was broken.

He explained, “Before, we donated or sold plastic recyclables to junk shops. The problem was they turned us away when the processor had a supply surplus. At the same time, the junk shops also wouldn’t accept our items when their storage was full. What do we do with our weekly collection?”

So, the volunteers turned over the marine waste to CENRO, which dumped them at the sanitary landfill. Unfortunately, scavengers picked up these plastic bottles and tried to sell them to junk shops and since they wouldn’t buy anymore, the same PETs ended up on the shore as marine litter.

Trash to cash

In 2022, the group stumbled upon an opportunity that would change its trajectory forever and, hopefully, make a dent in the marine pollution problem that Davao City grapples with. The Bantay Dagat Volunteers Association secured a P5 million grant from Japan, through the United Nations Healthy Oceans and Clean Cities Initiative (HOCCI), after its project proposal to make eco-blocks was approved.

The association used P1.3 million from the fund to purchase the crusher and shredder from China with the help of a local fabricator. They also bought a bottle crusher from a local fabricator for P300,000 and a hollow block maker and mixer at P80,000 each.

Now, all plastic waste is transported to the association’s 1,000-square-meter recycling facility in Daliao, Toril, about 15 kilometers from downtown Davao.

The PET and glass bottles are shredded and crushed before being added to the mixture of cement and sand to make hollow blocks and paver bricks. For each sack of cement, five kilos of shredded plastic is added, which can only produce 80 hollow blocks, which sell for P13.00 apiece. For pavers, the ratio of sand and crushed bottles is 60:40.

Eventually, the association plans on also processing plastic sachets by stuffing them into the PET bottles before feeding them into the shredding machine. But Mr. Bermejo said they haven’t found the perfect formula yet considering they only started on September 30, 2023, and the last quarter of last year was spent testing and perfecting their production.

“Cleaning the sachet is a meticulous process since you will clean each one to clear all the sand and debris. If not, they will dull the blades of the machine. Our machines use twelve 18-inch blades, which need to be sharpened regularly,” he said.

“But I know how plastic sachets contribute to marine pollution, so that’s our next task,” he added.

No mean feat

The association’s job is not easy.

Davao City has 34 coastal barangays stretching 60.1 kilometers from Barangay Lasang in the north and Barangay Sirawan to the south. These communities hug the Davao Gulf with a land area of 520,000 hectares and cover all Davao provinces.

Apart from the canals and drainage, the city also has the Davao River, the third largest in Mindanao, and several tributaries that wash junk, detritus, sweepings, and other debris to the shore.

So, every week, around 350 volunteers—armed with sacks, sticks, and their signature green uniforms—trek to the coast and begin the laborious (and sometimes thankless) task of picking up PETs and other waste from the shore. They also have certified divers cleaning the ocean floor.

“We conducted a waste analysis and characterization study with Ridge to Reef Consultants, and the plastic recovered in one Saturday is 24% of the total waste,” Mr. Bermejo said. “So, in 950 kilos, 216 kilos of that is plastic.”

Of the 24% of recovered marine plastics, 80% comprises PET bottles and 6% is glass.

A Typical Saturday Morning

The soft-spoken Bantay Dagat coordinator Marlon Elumbra has been busy barking orders to the volunteers to ensure that no trash is left behind at their clean-up point in Barangay 76-A, one of the highest population of coastal dwellers in the city. While he talked sternly and authoritatively to the volunteers, he reserved his charm for the residents.

“We are not here to make enemies. It’s difficult to convince the residents living along the coast to be more responsible with their waste. Although the barangay has a collection point, it would mean walking all the way to the designated area when they could simply dump the trash from their homes to the sea,” he lamented.

The volunteers started before 6 a.m., taking advantage of the low tide to cover as much ground as possible. By the end of their three-hour shift, the group collected 50 sacks of trash, with six carrying plastic bottles that would be delivered to the recycling facility for shredding.

Mr. Elumbra is responsible for five coastal barangays and rotates the volunteers every Saturday according to need. They have dedicated workers who will visit each purok (hamlet) to take photographs of the accumulated marine waste and file a report, which would then become the basis for scheduling a clean-up.

Mr. Elumbra said the project is a double-edged sword as residents feel unruffled about throwing their trash anywhere, knowing CENRO workers and Bantay Dagat volunteers will clean up after them.

“Of course, this area would be littered with trash again the next time we come here,” he said. “It’s a never-ending cycle unless the residents change their mindsets.”

The coordinator then shepherded the volunteers next to the sacks of collected waste for the final photo documentation to prove they had finished their task for the day. “We did our job here, but the barangay officials and the residents must do their share for our oceans. This is not for us but for the next generation,” he said.

A monumental problem

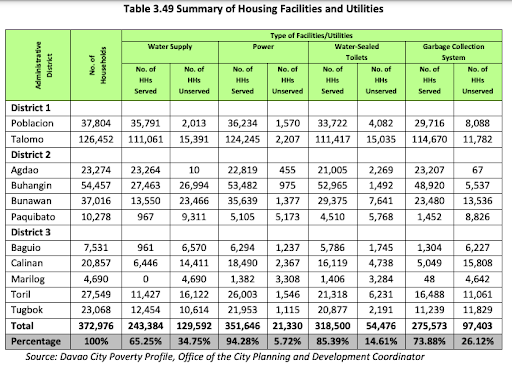

On average, Davao City generates more than 600 tons of waste daily, comprising 50% biodegradable, and 29% residuals, and the rest are recyclables and special waste. However, the volume easily shoots up to 1,000 tons during special occasions like the Kadayawan Festival or the Araw ng Dabaw primarily due to visitor influx.

In 2022, the City Environment and Natural Resources (CENRO) rolled out 12 garbage compactors the city government purchased at P10 million each. The new trucks, capable of hauling eight tons of waste, boosted its fleet from the previous three to 15. To ensure it reaches the last barangay, the city government also rented 100 trucks from private companies to augment its daily waste collection.

Nevertheless, garbage trucks could not logistically serve far-flung barangays due to the sheer distance. For instance, Barangay Buda, which borders Bukidnon province, is about two hours away from downtown. Presently, garbage trucks only make regular trips to about 125 of the 182 barangays.

According to CENRO, unserved households either burn, compost, recycle, or throw their waste anywhere.

Davao City has about 500 recycling companies and junkshops, including the informal sector, which help recycle or reuse 60,000 tons of waste yearly. But these private companies, along with the city’s efforts, are clearly insufficient judging from the 950 kilos of PETs and sachets the volunteers collect from the ocean and shore each week.

According to a World Bank study, the country produces 2.7 mln tons of plastic waste annually, and 20% of these end up as marine pollutants. The “tingi-tingi” culture also contributes to 163 million sachet pieces used daily.

Meanwhile, Duke’s Nicholas Institute ranked the Philippines third among the top plastic pollution contributors globally, generating 2.7-5.5 metric tons annually. With zero interventions, researchers anticipated plastic waste to reach nine million tons by 2040.

Lax implementation

Atty. Mark Peñalver, executive director of Interface Development Interventions for Sustainability, points to insufficient mechanisms in enforcing landmark laws like the Solid Waste Management Act and the Single-Use Plastics Ban Ordinance as the biggest culprit.

RA 9003 (The Ecological Solid Waste Management Act) mandates the 3R or Reduce, Reuse, and Recycle. Under the law, residents must segregate and sort their waste at-source. So, biodegradable waste would have been composted and recyclable materials handed over to the barangay’s Material Recovery Facility (MRF). This also explains why the volume of garbage, or 500 grams daily, contributed by each resident has not shrunk.

Unfortunately, only eight of the 182 barangays have a functional MRF and households do not practice composting, Peñalver said.

There are nearly 500,000 households in Davao City and they contribute 80% of the total waste emptied by garbage trucks at the 3.8-hectare sanitary landfill in Barangay New Carmen in Tugbok District, some 15 kilometers from the downtown area.

“Among the most obvious problems we’ve seen are the collection points. If properly managed, the collection point should be fenced to ward off stray dogs and scavengers,” Peñavler said.

Apart from open dumping where residents simply throw trash on a vacant lot, the location of the collection point is also a concern due to the absence of a buffer from the nearest canal. “So, if the truck is delayed, there is a danger of runoff, especially during rains,” he said. “When trash reaches the canals, they eventually end up on the ocean.”

The environmental group sees the relaxed enforcement of the Solid Waste Management Ordinance. In 2021, the lawmakers passed City Ordinance 0706-21, which increased penalties for non-segregation of garbage from P300 to P500. Erring business establishments, meanwhile, face a P5,000 fine for a similar violation.

Barangay officials are also deputized to issue citation tickets to violators, including residents who don’t follow the designated schedule for dropping trash at the collection points.

Peñavler said the “No to Single-Use Plastics Ordinance” was passed in 2021 and was supposed to be fully implemented in 2022. However, until now the CENRO still hasn’t released the Implementing Rules and Regulations (IRR).

The ordinance only covers cutleries, cups, egg trays, straws, and other non-biodegradable materials that eventually wash out to the sea. While grocery stores and shopping malls have transitioned to “biodegradable plastics,” IDIS said it’s not addressing the problem since they eventually break down into microplastics.

He also said the No to Single-Use Plastics Ordinance does not cover sachets and chichiriya (junk snack) packages.

“Instead of sachets, we are pushing for refilling stations at grocery stores, which is already being done in Quezon City. Eventually, the refilling stations will cascade to the sari-sari (sundry) stores to be nearer to the consumers,” he said.

In 2021, IDIS conducted a four-day Waste Assessment and Brand Audit, ranking the top brands with the most number of throwaway plastic waste, of the city’s rivers. The group found that the products of Coca-Cola, Rebisco, Liwayway Holdings, Procter and Gamble, Unilever, Nestlé, JBF Food Corp., Monde Nissin, NutriAsia, and Universal Robina Corporation make up the nearly 4,000 pieces of PETs, sachets, glass bottles, plastic bags, and toiletries collected.

Davao Eco-Blocks and Paver Bricks

Mr. Bermejo explained that while the city government was instrumental in forming the association, the extent of support they receive is limited for the allowance of the volunteers.

“Our recycling facility does not receive financial support, so we have to work hard to cover the cost of maintenance and operations,” he said.

For instance, to keep the selling price competitive, the association did not compute the energy cost of making the eco-blocks and eco-bricks. The shredder is a 20-horsepower machine requiring a three-phase electrical supply to run. In addition, they need to hire experts to sustain product quality.

These experienced hollow-block makers work as freelancers who collect P220 per sack. Unfortunately, their services are very much coveted, meaning the association sometimes loses them out to other companies.

He said the market is not the issue, considering they have backlogs and even had to turn away orders because the association could not meet the demand. For instance, he turned down the order for 5,000 pieces considering they could only produce 2,000 from their maximum yield of 800 pieces daily. However, they could only make 180 pieces daily due to a shortage of experts.

The problem is the monthly bills are rising in the meantime while the association gets bogged down by its inability to go full blast in its operations. Presently, he estimates that they need at least P60,000 for property rent, maintenance, operations, and utilities alone, excluding manpower. And the only solution he saw was to automate their operations to avoid overreliance on human labor.

Fortunately, the association became a beneficiary of a P1.5 million grant from the Department of Labor and Employment XI, which involves a fully automated machine that will enhance the facility’s production capacity.

“The machine we will get from DOLE is semi-automated, so we no longer require experts. The only manual labor involves loading the sand and mixture,” he said.

The daily yield for the semi-automated machine is 3,700 blocks, which can extend to 4,100 in eight hours of operation. Mr. Bermejo also shared that they might receive two more similar automated machines from DOLE XI under the same program, allowing the association to triple its production potential to at least 12,000 blocks daily.

“With that capacity, I am no longer reluctant to market our products under the brand name Davao Eco-Blocks and Paver Bricks because I know we can meet our orders,” he said.

For now, the association relies on word-of-mouth advertising. Eventually, when the automated machines are fully operational, Mr. Bermejo plans on reaching out to the Philippines Institute of Civil Engineers where he has been a member for 12 years, as well as the local government units in the region.

“The LGUs are now developing eco-parks. So, what if they use our paver bricks and hollow blocks? Then, literally, you can proudly say that this is an eco-park because we use recycled blocks and bricks here,” he said.

(This story is part of a micro-grant from FYT Media and the Philippine Network of Environmental Journalists following a climate solutions and capacity enhancement training workshop on November 23-24, 2023, in Baguio City).

REFERENCES:

- Davao City Comprehensive Development Plan (2018-2022). Ecological Profile (Volume 1). https://cpdo.davaocity.gov.ph/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Ecological-Profile-2018-2022.pdf

- CENRO (May 2016). Collaboration Program with the Private Sector for Disseminating Japanese Technology for Waste-to-Energy System in Davao City. JICA. https://openjicareport.jica.go.jp/pdf/12302113.pdf